Chapter XIII

And So To War

Introduction

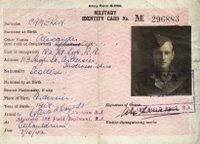

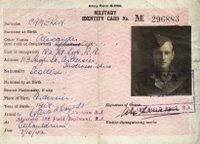

For almost seven years, until my release in May 1946, I served in the Gunners. So much happened during that time that I could not possibly commit all my memories to paper without causing boredom in the reader. What follows will be of a strictly anecdotal nature; namely the highlights of what for me were seven very happy years among comrades of the finest kind. The influence of the camaraderie I found in the Army (and the Navy too as you will hear later) has remained with me to this day and has certainly helped me along life's way.

Do keep it in mind too, that I did not keep a diary, that war-time restrictions on newspapers were pretty severe and that individual soldiers had a very restricted view of what was going on in the world. There were times when we would not see a newspaper for weeks on end and what was in them was, naturally, censored. In my own case several of the positions I held carried the official Secrets Act requirement of silence.

A) The first Month

On Sunday 3rd September 1939, the day war was declared, the 78th Field Regiment R.A. was gathered in the drill hall Grindlay Street, Edinburgh (opposite the Usher Hall) preparing to move out to a secret destination - we, of the lower ranks, knew not where! Wives, sweethearts, mothers, fathers, children and other relations of the soldiers were in attendance outside the Hall to say farewell to their loved ones. I was the only soldier who did not belong to Edinburgh so I could look on at the melee somewhat objectively. Especially was this so when at 11 am after the bells of St. Cuthbert's and St. Johns' Churches had ceased ringing, the air raid sirens screeched their warning of imminent air attack! Now the scene became one of bedlam within and without as civilians and soldiers sought shelter where there was none. I stood calmly in the quarter-masters' office looking out over the hall packed with panicking folk. The Assistant Adjutant, a young Writer to the Signet of a well known west end family, came rushing in telling me that we were all to wear our gas masks. He had no idea how to adjust his own and sought my help. He had obviously not had the practice which U/A/L/Bdr. Cameron had during the recent weeks. How alarmed he was when eventually the gas mask was on his face with all the straps adjusted properly. I had to assure him that he would not suffocate. The 'all clear' sounded on the sirens about 11.5 am and gas masks were removed with thankfulness.

Later, after a real Army dinner (never called 'lunch') eaten from our mess tins we had all to parade in the Usher Hall for medical inspection - only those found to be Grade A1 would be permitted to continue with a Field Regiment. On entering the hall we were ordered to occupy every second row of seats and to remove all clothing above the belt. The Medical Officer (M.O.) arrived with the Regimental Sergeant Major (R.S.M.). As they reached each row the R.S.M. ordered 'drop trousers and pants and raise the arms above the head'. Thereafter the M.O. walked along the vacant row looked at each poor soul with his arms in the air and feeling more embarrassed than he had ever done before and without exception the medical opinion expressed was 'all A1'. With that the R.S.M. gave the order 'Now get dressed'. You can just imagine how we all felt but that was all the medical we had!

Our 'secret' destination was Currie and Hermiston scarcely four miles from Grindlay Street: What a let down! The quarter-master's staff formed part of what was known as regimental headquarters and as such we were accommodated in horse stables at Hermiston. Our bedding consisted of three 'blankets - woollen army' which when properly folded (as taught during the first camp) could provide five layers of blanket below and three on top or vice versa depending on the sleeping quarters. On the stable floor of cobble stones the three blankets were totally inadequate. After the first uncomfortable and sleepless night I raised the matter with the R.Q.M.S. but he had no power to give us additional blankets. I therefore 'brass necked it' (to use an army expression) gained admission to the Adjutant by the simple process of knocking at his office door and entering. He was a young Advocate whom I had met in Parliament House on one occasion and he answered my plea by issuing an order to the R.Q.M.S. that all Regimental H.Q. staff were to have an additional half dozen blankets! Wasn't I popular with the plumbers, carpenters, train drivers and others who were my colleagues.

At 9 am. on the first Saturday as 'real' soldiers the members of Headquarters Troop were required to parade before the R.S.M. He ordered us to remove our caps ('cheese - cutters' as they were called), came along the lines of soldiers examining the many and varied hair styles; in front of each man he ordered 'Hair Cut'. When he came to me and saw the length of my fair locks his command was quite straight forward namely 'get if off!'. That afternoon in a barber shop which I used to pass going down Lothian Road of a morning, but had never used for lack of funds, the barber said you'll need a 'short back and sides'. 'No' I replied. 'Take it all off'. I left the shop with the leather lining of my cap stuffed with folded newspaper to prevent the thing falling down over my eyes! On the Monday morning when the R.S.M. came in to inspect my 'short back and sides' he nearly had a fit and addressed me in words which I will not repeat here! Three years, or more later I was to become his Adjutant!

About the middle of September I had to proceed with the R.Q.M.S. the Quarter-Master himself (who was a commissioned officer), Bill Irons and said Adjutant to Burntisland to which one of our Batteries had been moved. For what purpose I do not recall: But on the return journey just as we disembarked from the ferry at South Queensferry we witnessed the first attempt by 'jerry' to bomb and destroy the Forth Bridge. The German bombers had little success and were soon chased out of the area by fighters from the R.A.F. base at Turnhouse. As mere sightseers we saw the aerial 'dog fights', heard the anti aircraft guns firing and saw their shells exploding in the sky, but did not see the Forth Bridge tumbling down! For a record of this first German attack the reader will have to look elsewhere.

on the return journey just as we disembarked from the ferry at South Queensferry we witnessed the first attempt by 'jerry' to bomb and destroy the Forth Bridge. The German bombers had little success and were soon chased out of the area by fighters from the R.A.F. base at Turnhouse. As mere sightseers we saw the aerial 'dog fights', heard the anti aircraft guns firing and saw their shells exploding in the sky, but did not see the Forth Bridge tumbling down! For a record of this first German attack the reader will have to look elsewhere.

On 19th September my Grandfather passed away having been ill, for the first time in his long life, during the preceding four weeks. Leave was granted so that I could attend the funeral in Ardersier which I did and enjoyed the few days with my Mother and Father at home in 113. I was not to see them again until March 1942.

The news on returning to the Regiment was that our Commanding Officer had committed suicide! A new C.O. Lieutenant Colonel W.A. MacLellan, of the famous Steel Pipe Making company in Glasgow, had been appointed and was already installed.

The previous C.O. had put my name forward for a Commission and I had been interviewed in Stirling Castle. When Col. MacLellan received the letter informing him that I had been selected he immediately sent for me, told me that he wanted me to stay with the Regiment that he wanted me to take over responsibility for the Regimental office and with this in mind had already arranged a place for me on an Artillery Clerks course in Woolwich the home of the Gunners. So - What could I do? In my lowly position. I had to bow to my superior's wishes. The course was to begin at the beginning of October and would last for six weeks.

B) Learning to be an Artillery ClerkAt Woolwich forty soldiers from Gunners to Sergeants assembled for the course. Accommodation and feeding was of pre war standard: quite comfortable and plain with lots of 'plum duff' every day. The training was given by excellent lecturers, who helped us greatly by issuing copies of their lectures. This pleased me greatly. The administration of a Field Regiment was covered in depth and the law governing the Army as contained in the Manual of Military Law was 'drilled' into us. Only one subject troubled me and that was type writing! We were expected to pass out at the end of the course with the proven ability to type at the speed of 40 words per minute. No instruction was given but for those like me who could not type there was a roomful of Barlock typewriters available for learners and practice every evening after 6pm. At the end of the course we had to type a piece from that day's issue of the Daily Express and somehow or other I passed! The other subjects gave me no difficulty and I arrived back at Hermiston with a 'D' certificate in my pocket 'D' = Distinction.

Immediately I was promoted to the proud rank of Sergeant (A.C) which gave me three stripes and a gun on each arm and raised my pay from two shillings to 8/9d per day.

During that time in Woolwich we were free on Saturdays and Sundays and this gave me the opportunity of seeing something of London. The River Thames and much of the City were 'protected' at that time by a great many barrage balloons floating in the sky - a constant reminder that we were at war although the Germans had not yet attacked: nor had we of course during what was known as the 'phoney war'. I first experienced rowing a skiff on the serpentine - a wonderful experience after I got accustomed to the moving seat. After a few practices it became clear that this narrow boat could be propelled through the calm waters of a lake at a far higher speed than anything I could achieve in my dear old dinghy. To my horror one day when travelling at high speed I struck another boat broadside on. It capsized, the rower was in the water which gladly was quite shallow so when he stood up he towered above me and really gave me 'what for'!

experience after I got accustomed to the moving seat. After a few practices it became clear that this narrow boat could be propelled through the calm waters of a lake at a far higher speed than anything I could achieve in my dear old dinghy. To my horror one day when travelling at high speed I struck another boat broadside on. It capsized, the rower was in the water which gladly was quite shallow so when he stood up he towered above me and really gave me 'what for'!

I deserved it! Fortunately the other boat was not damaged - nor was mine. I left the Park, having had a second 'telling-off' from the boat attendant, feeling very ashamed of myself.

The Tower of London, Buckingham Palace, Trafalgar Square with all its pigeons, the National Gallery and its Art treasures, Hyde Park Corner with its speakers of every persuasion. The Mall, the Planetarium and Madame Taussaudes were all visited during my six free weekends, sometimes in the company of another course member. I got to know the London Underground and the London bus routes remarkably well. Yes, it was a thoroughly enjoyable way in which to commence one's army career. Apart from the above mentioned 'sights'. I had the privilege of visiting Westminster Abbey and St. Paul's Cathedral and heard that famous preacher Dick Sheppard in his lovely church of St. Martin's in the Fields. The crypt of the latter was being used as a soldiers' canteen and I benefited from that.

On being promoted to the rank of Sergeant I had, of course, to transfer myself to the Sergeants' Mess where, happily, I was well received. Whether this was due to the fact that I would daily be in contact with the C.O., Second in Command and Adjutant or to their previous knowledge of me in the Q.M. stores I do not know. I like to think it resulted from a general impression of 'wee Alex' - the wee fella from the Highlands - formed during our happy Friday evening training sessions in the T.A.

C) To Selkirk and PiddlehintonWe were not long in Hermiston and Currie before being moved to Selkirk and Galashiels where woollen mills had been requisitioned ('taken over' in ordinary language) for army purposes. Accommodation was of course fairly basic - large barrack - like halls from which the machinery had been removed. The 'other ranks' slept on paliasses (mattresses filled with straw) laid on the floor: Sergeants in smaller units on wooden beds. The large vat in which wool was dyed, when the mill was in operation, was filled with warm water and this provided us with a communal bath capable of accommodating two dozen men at a time in water about 3 feet deep. The C.O. had ordered that all ranks were to have a bath at least once a week so the vat was full every evening; with 550 of an establishment that meant that almost 80 men were washed and bathed every evening all in the same water! No harm came to any of us. The water was changed every day.

Feeding was of the highest standard as the army pre-war ration allowance still applied so we were fed like fighting cocks.

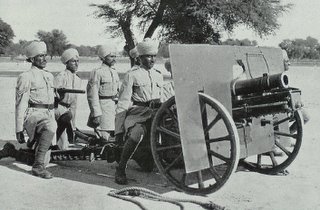

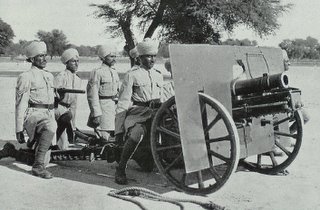

Soon after arrival in Selkirk o ur old 18 pounder guns were withdrawn, and so we were told, we were the first Regiment to be issued with what was to become recognised as the finest field ordnance in the British Army, namely the 25 pounder. That winter was one of very severe frost in the Borders and the oil in the buffer recuperator systems (the recoil mechanism) of the brand new guns froze solid. The casings were severely cracked, the guns useless! How old Colonel MacLellan fumed, Soon engineers arrived from Woolwich, the guns were removed and almost immediately replaced by new guns in which, we were assured, the oil would not freeze.

ur old 18 pounder guns were withdrawn, and so we were told, we were the first Regiment to be issued with what was to become recognised as the finest field ordnance in the British Army, namely the 25 pounder. That winter was one of very severe frost in the Borders and the oil in the buffer recuperator systems (the recoil mechanism) of the brand new guns froze solid. The casings were severely cracked, the guns useless! How old Colonel MacLellan fumed, Soon engineers arrived from Woolwich, the guns were removed and almost immediately replaced by new guns in which, we were assured, the oil would not freeze.

In Selkirk we had our first taste of the warm and generous hospitality which was extended by the local people to soldiers within their midst during the whole of the war. The Churches, Woman's Voluntary Service, British Legion all went to great lengths to entertain ( and feed! ) the troops.

No sooner had January 1940 come to a close than we were ordered to move to a place with the extra-ordinary name of Piddlehinton in Dorset. So on its first long distance move the 78th proceeded, at the prescribed speed of 12-1/2 m.p.h. and with a distance of approximately 100 yards between each vehicle in the convoy, towards this mysterious place. There were 150 vehicles in the Regiment of which 24 were gun-towers. After about five days on the road we completed the 450 mile journey: I had enjoyed it very much sitting as a passenger in a comfortable Hunter wireless truck filled not with wireless sets but with office equipment, files, stationery etc.

Two batteries and Regimental H.Q. were allocated accommodation in halls of various kinds, requisitioned mansion houses and such like in the village of Piddlehinton which we soon discovered was located, yes, on the River Piddle about 5 miles north of Dorchester. The third battery were in Puddletown just a couple of miles down river! The river was in fact no more than a burn.

In Dorset the local drink was Cider and as the pubs did not sell Scottish beer the boys indulged in the cider, encouraged by the locals. Many had to be carried home at night by their mates as the cider was much stronger than any beer to be found in the howffs of Edinburgh. In an effort to control the drinking the C.O. introduced a 10 PM curfew which did not meet universal approval! I still remember typing the order to be placed on all notice boards.

Not being a drinker I used to accompany a few of my Sergeant friends to canteens which had been organised by dear old ladies in church and other halls. They were astonished when we first arrived on the scene that we were not wearing kilts. The locals seemed to be under the impression that all Scotsmen wore the kilt and, moreover, had heather growing between their toes. We spent over three months in Dorset preparing for action. The spring weather was lovely, the apple trees blossoming gloriously. We enjoyed our sojourn in that part of England yet always wondering when the fighting was going to begin: and where. It began so far as the British forces were concerned not by Hitler landings in the UK by sea and air as we had anticipated but when he ordered his forces to move west towards the Atlantic over Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg, and France.

D) The second B.E.F. (British Expeditionary Force)Towards the end of May the Regiment was ordered to move to the Aldershot area. There we were issued with all the extra paraphernalia required by a unit going into action: tons and tons of equipment some of which we had never seen before. At that time the British Expeditionary force was evacuating from Dunkirk and at Aldershot we saw truck after truck arrive with survivors of the B.E.F. some dressed only in their trousers some indeed only in their 'shirts' truly a sorry sight. And here we were fully equipped and 'roaring' to go - but where?

Churchill answered that question when he announced he was sending the second B.E.F. to France to stop Hitler! And so on 5th June 1940 the Fifty-Second (Lowland) Division of which we were part and the 1st Canadians embarked from Southampton and Plymouth. On 12th June we were able to see on the cinema screen in Southampton all 24 of our 25 pdr. guns being lifted individually by derrick on to a large cargo boat! The Second B.E.F. had to turn and flee - for the record I might say that we lost only one vehicle and the guns did not even reach a French port when the Captain of the ship wisely decided to turn back.

Soon the Regiment was directed to East Anglia to defend the shores of old England! The Canadians were down in Kent and together these Divisions were the only fully equipped and manned units of the British Army at that time. We in 78th had only 24 rounds per gun, the normal peace-time holding, while the few soldiers carrying rifles, mainly for guard duty on gun and vehicle parks had six rounds each the same as the officers who carried Smith and Wesson .38 pistols.

E) East Anglia

R.H.Q. was stationed in the small town of Fakenham the people of which took the 'Scottish boys' to their hearts. The three batteries were located in positions, such that one had its guns always 'laid' on Marham aerodrome while the other two were eastwards towards Great Yarmouth and Gorleston those great herring ports.

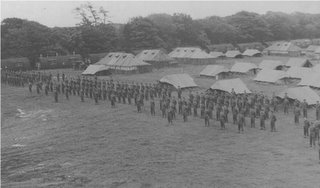

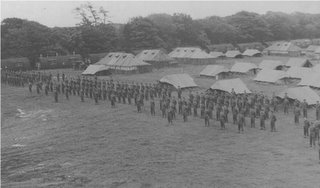

Accommodation was in bell tents which were erected over a large hole in the ground three feet deep and of the same circumference, or so, as the tent. This was t o provide shelter against anything other than a direct hit. There was a good deal of bombing by German aircraft but only against aerodromes. We were told that the spire of Ely Cathedral and its copper roof were being used by the enemy as navigational guides and no doubt that was the case for no attempt was made to bomb Ely.

o provide shelter against anything other than a direct hit. There was a good deal of bombing by German aircraft but only against aerodromes. We were told that the spire of Ely Cathedral and its copper roof were being used by the enemy as navigational guides and no doubt that was the case for no attempt was made to bomb Ely.

At this stage our Divisional Medical Officers were finding more and more men inflicted with venereal disease and this created more worry among the Commanding Officers than a German landing would have done. What was to be done? In the end it was decided to ask the Reverend Roland Selby Wright, Minister of the Canongate Kirk in Edinburgh and Warden of the famous Canongate Boys Club to use his influence with the men of the Division. And so it was that the Cathedral at Kings Lynn saw every officer and other rank of the Division in relays - fill its pews and choir stalls while they listened to R.S.B. preach a sermon on true love. He had a most wonderful way of getting his message home to men: we were reminded of the wives and mothers, sisters, fathers, brothers, grannies and granddads at home in Edinburgh and of the heart-breaking effect news of V.D. in their loved one far from home would have. I don't suppose his appeal for celibacy was answered by all his hearers but the doctors saw an immediate drop in the number of cases and never again did the same problem arise.

In the Division we also had as Senior Padre the Rev. Joseph Gray M.A.,T.D. (later to marry Wilma and myself) and Rev Leonard Small (of St. Cuthberts). With their support I was able to obtain large quantities of C of S. Huts Notepaper and envelopes from 121 George Street, Edinburgh and to distribute these among the troops as an encouragement to write home regularly. All the officers became involved in my 'scheme' and this certainly helped tremendously in maintaining morale over a number of years.

On one of the occasions when the Adjutant had me with him down at the Coast several bodies of Germans were washed ashore, probably air crew who had been shot down. This resulted in a rumour that the Germans 'had tried to land and been beaten back' as one paper had it.

However the C.O. had news from the War office that the Germans were mustering barges and similar craft in Holland and invasion was to be expected soon. Guards at all posts were doubled and we all lived in great expectation.

However, there nearly was a mutiny in the Division! We had been issued for several weeks with nothing but tinned fish, herring, pilchards, salmon and tuna, for breakfast, dinner and tea! What a blessing the local ladies had set up their canteens and that we had access to 'good food' like sausage and mash, beans on toast, pork pies and so on. So bad was the situation that each Regiment was visited by no less a person that the King accompanied by our G.O.C. General Ritchie. The latter told each parade that the government apologised for the daily offerings of tinned fish but, he said, food intended for the United Kingdom from Canada and U.S.A. was being lost at sea every day. What we were receiving had come from government reserves. This did nothing to assuage the hunger of the young men who had until recently been fed nothing but the best.

Soon after this we were moved again this time to Scotland!

F) Back to Scotland

Our move back to Scotland included a firing camp at Otterburn in the Borders which lasted almost two weeks. This really allowed the boys on the guns to let off steam and the rest of us to see them in action firing live ammunition. It was a pleasant break in good weather. Our destination was Falkirk where we were accommodated in halls of all sorts . R.H.Q. was in an office right in the centre of Falkirk. One of those whose livelihood had been taken away from him was a Mr Jimmy Turpie a dancing instructor who told me, he had been a stoker in the Navy in World War I. He kept coming to see me about the possibility of allowing him to resume dancing classes in one or more of the halls which he had previously rented. There was nothing I could do about that but I was able to help him sort out his Income Tax affairs which were in a shocking state. In return he and his good lady, Mary extended kind hospitality to me and Jimmy even taught me how to do the quick-step, fox-trot, waltz and tango! I was never very good at these but Jimmy must have had an ulterior motive - or maybe it was Mary. Their daughter Jean was engaged to a Falkirk lad who played for the local football team but Jimmy entered me as her partner for a competition dance at the local ice-rink. To my utter astonishment we won first place in the quick step and slow fox-trot! Great rejoicing in the Turpie family and much leg-pulling in the Sergeants Mess! When I heard soon after this that the engagement was to be broken off I had to be quite firm and told Mother and Daughter that I was not in the slightest bit interested. So the engagement ran the usual course and Jean and her fiancee married. (He became an Electrical Engineer and worked in the Electricity Supply Industry as I was to do).

Actually the people of Falkirk were most kind to the troops providing all sorts of entertainment. At the ice rink one quarter of the skating area had been boarded over and fenced off from the skaters. The local W.V.S. were as always, quite wonderful. During this period I acquired a pair of skating boots and had instruction from some of my colleagues who could already skate. But I never did become an expert!

We were in Falkirk for only three months when the Regiment was moved to Dunblane and Auchterarder. From here it was easy to gain access to the firing ranges on Shefiffmuir. I have no recollection of anything exciting happening in Dunblane except perhaps that we were selected to participate in a service broadcast from St. Blanes Church at which Ronald Selby Wright preached an inspiring sermon and I was introduced to a prominent person in the B.B.C (whose name I've forgotten) who suggested I join his organisation as a news reader on the Empire service when war was ended. (We still had an Empire at that time!) He would personally recommend me because of my Inverness accent. But I did not take up that offer.

The next move was to Haddington in East Lothian where I became friendly with the late Rev. Robin Mitchell minister of the church beside the Regimental office. He was a great outdoor man and an expert on the flora and fauna of the area,. It was with him while we were fishing on the River Tyne one evening that I saw, for the only time, the death dance of the flies. Literally millions of flies gathered along the still waters of the river in the shape of a cone towering perhaps twenty or thirty foot high. The noise of humming as they rose into the air was awesome: the vertical climb lasted for about five minutes and then all at once the whole cone collapsed and fell into the Tyne. A truly moving experience which I have never forgotten. Robin and his wife were most kind to me all the time I was in Haddington. One of my clerks was the son of a Minister who loved to play the organ so he was appointed organist for all church parades -although he claimed to be an atheist. Jimmy Milne was his name and before the war he had become famous by marrying while still under the age of 25 contrary to the regulations governing employees of the Commercial Bank for which he worked. He was dismissed but appealed to the Court of Session on the grounds that the regulations were 'Contra libertatem matrimonii' The law of Scotland regarded as illegal any restraints put on marriage - it probably still does; I hope so anyway. I used to give him permission on a Saturday evening to leave his quarters above the office in order to practice 'for tomorrow'. Little did he know that five or six of us including the Adjutant and Second-in-Command crept into the back seat of the church while Jimmy sat in candlelight at the organ playing beautiful pieces of music from the classics, Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Handel among them. For an hour we would sit enchanted by the wonderful music and then creep silently out into the night. If the organist had known he would have risen and left. Then one night the noise of aircraft filled the skies: enemy bombers on their way to Clydebank and Gourock but we did not know that. The anti-aircraft guns in the district were 'pooping off' all around Haddington while searchlights pierced the darkness. One bomber was hit and crash landed in a field outside the town but not before it had dropped five bombs all of which hit Military targets - his good luck and not good judgement. The quarter-masters store in a tenement in the centre of Haddington had a direct hit and was set ablaze. My friends Joe and Bob managed to escape by 'shinning' down a drain pipe. Across the street an unexploded bomb fell through the roof of a tenement and landed at the foot of the stairwell. In that tenement another of my boys - the most gentle of souls - had rented a room and kitchen for himself and his bride of a few days. He picked up the 50 kg bomb and carried it out the back door, across the back green and dropped it over the boundary wall - all in order that his lovely wife should not be killed. The three other bombs landed in the main car park and the gun park and although they exploded no damage was done.

the darkness. One bomber was hit and crash landed in a field outside the town but not before it had dropped five bombs all of which hit Military targets - his good luck and not good judgement. The quarter-masters store in a tenement in the centre of Haddington had a direct hit and was set ablaze. My friends Joe and Bob managed to escape by 'shinning' down a drain pipe. Across the street an unexploded bomb fell through the roof of a tenement and landed at the foot of the stairwell. In that tenement another of my boys - the most gentle of souls - had rented a room and kitchen for himself and his bride of a few days. He picked up the 50 kg bomb and carried it out the back door, across the back green and dropped it over the boundary wall - all in order that his lovely wife should not be killed. The three other bombs landed in the main car park and the gun park and although they exploded no damage was done.

When the C.O. heard what Gunner Bartlett had done with the unexploded bomb he nearly had a fit! But while he contemplated a court martial decided in the end simply to reprimand Bartlett. After the C.O. had explained how dangerous and therefore wrong it was to handle an unexploded bomb I remember Bartlett saying in his quiet way "and what would you have done, Sir, if your wife had been similarly placed?" The reprimand was merely a warning 'not to do the same again'!

Our C.O. Colonel MacLellan was moved and replaced by one who had been a Gunnery Officer at Larkhill, near Salisbury - the school of gunnery. He was a real fire brand! No sooner had he arrived than he was out inspecting every troop, every battery and, almost, every gun. It was evident that a disciplinarian had arrived as I typed order after order about every conceivable activity to go out to Battery Commanders. One of the first was that every member of the Regiment regardless of rank would parade on the nearest gun park at 6. am for physical 'jerks' under a P.T. instructor and whatever the weather. A foretaste of Monty's regime! You can probably imagine how clerks and cooks unaccustomed as they were to daily drills or parades reacted. But in the Army orders are orders. The P.T. Instructor for Regimental H.Q. was no less a person than the C.O. dressed in shorts and singlet. He had us hard at it for 30 minutes each morning before we were allowed to wash and shower at the out door toilet arrangements - cold water was freely available from a tap set above a metal wash hand basin.

Before the end of the first week he asked me to come in and bring my personal file. I knew not what was in store. After reading through it he demanded to know why I had not gone for the officer's training course offered in 1939 as I was just wasting my talents in this present job! My explanation was, of course accepted but he told me that he personally was going to arrange for me to go O.C.T.U. (Office Cadet Training Unit) as soon as possible. Meantime I was to go out to 181 Battery as a gun sergeant, learn all I could about the 25 pdr and ballistics and generally become a 'real gunner' to justify, as he put it the wearing of a gun on my arms! So off I went and did as the C.O. had told me to do. The gun itself and every part of it had to be mastered as also the trailer, in which 24 rounds of ammunition were carried, and the GUY gun-towing vehicle which not only pulled the trailer and gun but carried the gun crew of six including myself. Up until now the army had not let me loose among things mechanical and I revelled in this new found interest. There were handbooks to study, gun drill books to read and absorb and a detailed maintenance manual in relation to the Guy. I determined that before ever going to O.C.T.U. I would be a 'real gunner' as the C.O. had ordered and with the co-operation of my crew of five men and my fellow sergeants I like to think I was. We had several opportunities of firing live ammunition at Otterburn and Sheriffmuir. It was at the latter that my hearing was damaged. There was mist on the target area in the hills, the range was 10,000 yards and to reach this the layer (known as No. 3 on the gun) elevated the barrel to the required angle, I realised it was now fowling the camouflage net and proceeded to unlace the net to allow free movement of the barrel when the gun fired, the order to fire came as a shout from the Command Post and my layer without waiting for me to return to the No.1's position at the trail of the gun and then shout 'Fire', pulled the trigger. My head was about six inches from the barrel as the shell roared away into the sky. The blast knocked me out and when I came to I was at the Command Post, being cared for by a First Aider, with blood coming from each ear. Soon I was in Stirling Infirmary but was discharged that evening. For several months I suffered pains in my ears but when the call came for me to proceed to O.C.T.U. the doctor declared me A1 and off I went.

G) O.C.T.U. (Officer Cadet Training Unit)

And So To War

Introduction

For almost seven years, until my release in May 1946, I served in the Gunners. So much happened during that time that I could not possibly commit all my memories to paper without causing boredom in the reader. What follows will be of a strictly anecdotal nature; namely the highlights of what for me were seven very happy years among comrades of the finest kind. The influence of the camaraderie I found in the Army (and the Navy too as you will hear later) has remained with me to this day and has certainly helped me along life's way.

Do keep it in mind too, that I did not keep a diary, that war-time restrictions on newspapers were pretty severe and that individual soldiers had a very restricted view of what was going on in the world. There were times when we would not see a newspaper for weeks on end and what was in them was, naturally, censored. In my own case several of the positions I held carried the official Secrets Act requirement of silence.

A) The first Month

On Sunday 3rd September 1939, the day war was declared, the 78th Field Regiment R.A. was gathered in the drill hall Grindlay Street, Edinburgh (opposite the Usher Hall) preparing to move out to a secret destination - we, of the lower ranks, knew not where! Wives, sweethearts, mothers, fathers, children and other relations of the soldiers were in attendance outside the Hall to say farewell to their loved ones. I was the only soldier who did not belong to Edinburgh so I could look on at the melee somewhat objectively. Especially was this so when at 11 am after the bells of St. Cuthbert's and St. Johns' Churches had ceased ringing, the air raid sirens screeched their warning of imminent air attack! Now the scene became one of bedlam within and without as civilians and soldiers sought shelter where there was none. I stood calmly in the quarter-masters' office looking out over the hall packed with panicking folk. The Assistant Adjutant, a young Writer to the Signet of a well known west end family, came rushing in telling me that we were all to wear our gas masks. He had no idea how to adjust his own and sought my help. He had obviously not had the practice which U/A/L/Bdr. Cameron had during the recent weeks. How alarmed he was when eventually the gas mask was on his face with all the straps adjusted properly. I had to assure him that he would not suffocate. The 'all clear' sounded on the sirens about 11.5 am and gas masks were removed with thankfulness.

Later, after a real Army dinner (never called 'lunch') eaten from our mess tins we had all to parade in the Usher Hall for medical inspection - only those found to be Grade A1 would be permitted to continue with a Field Regiment. On entering the hall we were ordered to occupy every second row of seats and to remove all clothing above the belt. The Medical Officer (M.O.) arrived with the Regimental Sergeant Major (R.S.M.). As they reached each row the R.S.M. ordered 'drop trousers and pants and raise the arms above the head'. Thereafter the M.O. walked along the vacant row looked at each poor soul with his arms in the air and feeling more embarrassed than he had ever done before and without exception the medical opinion expressed was 'all A1'. With that the R.S.M. gave the order 'Now get dressed'. You can just imagine how we all felt but that was all the medical we had!

Our 'secret' destination was Currie and Hermiston scarcely four miles from Grindlay Street: What a let down! The quarter-master's staff formed part of what was known as regimental headquarters and as such we were accommodated in horse stables at Hermiston. Our bedding consisted of three 'blankets - woollen army' which when properly folded (as taught during the first camp) could provide five layers of blanket below and three on top or vice versa depending on the sleeping quarters. On the stable floor of cobble stones the three blankets were totally inadequate. After the first uncomfortable and sleepless night I raised the matter with the R.Q.M.S. but he had no power to give us additional blankets. I therefore 'brass necked it' (to use an army expression) gained admission to the Adjutant by the simple process of knocking at his office door and entering. He was a young Advocate whom I had met in Parliament House on one occasion and he answered my plea by issuing an order to the R.Q.M.S. that all Regimental H.Q. staff were to have an additional half dozen blankets! Wasn't I popular with the plumbers, carpenters, train drivers and others who were my colleagues.

At 9 am. on the first Saturday as 'real' soldiers the members of Headquarters Troop were required to parade before the R.S.M. He ordered us to remove our caps ('cheese - cutters' as they were called), came along the lines of soldiers examining the many and varied hair styles; in front of each man he ordered 'Hair Cut'. When he came to me and saw the length of my fair locks his command was quite straight forward namely 'get if off!'. That afternoon in a barber shop which I used to pass going down Lothian Road of a morning, but had never used for lack of funds, the barber said you'll need a 'short back and sides'. 'No' I replied. 'Take it all off'. I left the shop with the leather lining of my cap stuffed with folded newspaper to prevent the thing falling down over my eyes! On the Monday morning when the R.S.M. came in to inspect my 'short back and sides' he nearly had a fit and addressed me in words which I will not repeat here! Three years, or more later I was to become his Adjutant!

About the middle of September I had to proceed with the R.Q.M.S. the Quarter-Master himself (who was a commissioned officer), Bill Irons and said Adjutant to Burntisland to which one of our Batteries had been moved. For what purpose I do not recall: But

on the return journey just as we disembarked from the ferry at South Queensferry we witnessed the first attempt by 'jerry' to bomb and destroy the Forth Bridge. The German bombers had little success and were soon chased out of the area by fighters from the R.A.F. base at Turnhouse. As mere sightseers we saw the aerial 'dog fights', heard the anti aircraft guns firing and saw their shells exploding in the sky, but did not see the Forth Bridge tumbling down! For a record of this first German attack the reader will have to look elsewhere.

on the return journey just as we disembarked from the ferry at South Queensferry we witnessed the first attempt by 'jerry' to bomb and destroy the Forth Bridge. The German bombers had little success and were soon chased out of the area by fighters from the R.A.F. base at Turnhouse. As mere sightseers we saw the aerial 'dog fights', heard the anti aircraft guns firing and saw their shells exploding in the sky, but did not see the Forth Bridge tumbling down! For a record of this first German attack the reader will have to look elsewhere.On 19th September my Grandfather passed away having been ill, for the first time in his long life, during the preceding four weeks. Leave was granted so that I could attend the funeral in Ardersier which I did and enjoyed the few days with my Mother and Father at home in 113. I was not to see them again until March 1942.

The news on returning to the Regiment was that our Commanding Officer had committed suicide! A new C.O. Lieutenant Colonel W.A. MacLellan, of the famous Steel Pipe Making company in Glasgow, had been appointed and was already installed.

The previous C.O. had put my name forward for a Commission and I had been interviewed in Stirling Castle. When Col. MacLellan received the letter informing him that I had been selected he immediately sent for me, told me that he wanted me to stay with the Regiment that he wanted me to take over responsibility for the Regimental office and with this in mind had already arranged a place for me on an Artillery Clerks course in Woolwich the home of the Gunners. So - What could I do? In my lowly position. I had to bow to my superior's wishes. The course was to begin at the beginning of October and would last for six weeks.

B) Learning to be an Artillery ClerkAt Woolwich forty soldiers from Gunners to Sergeants assembled for the course. Accommodation and feeding was of pre war standard: quite comfortable and plain with lots of 'plum duff' every day. The training was given by excellent lecturers, who helped us greatly by issuing copies of their lectures. This pleased me greatly. The administration of a Field Regiment was covered in depth and the law governing the Army as contained in the Manual of Military Law was 'drilled' into us. Only one subject troubled me and that was type writing! We were expected to pass out at the end of the course with the proven ability to type at the speed of 40 words per minute. No instruction was given but for those like me who could not type there was a roomful of Barlock typewriters available for learners and practice every evening after 6pm. At the end of the course we had to type a piece from that day's issue of the Daily Express and somehow or other I passed! The other subjects gave me no difficulty and I arrived back at Hermiston with a 'D' certificate in my pocket 'D' = Distinction.

Immediately I was promoted to the proud rank of Sergeant (A.C) which gave me three stripes and a gun on each arm and raised my pay from two shillings to 8/9d per day.

During that time in Woolwich we were free on Saturdays and Sundays and this gave me the opportunity of seeing something of London. The River Thames and much of the City were 'protected' at that time by a great many barrage balloons floating in the sky - a constant reminder that we were at war although the Germans had not yet attacked: nor had we of course during what was known as the 'phoney war'. I first experienced rowing a skiff on the serpentine - a wonderful

experience after I got accustomed to the moving seat. After a few practices it became clear that this narrow boat could be propelled through the calm waters of a lake at a far higher speed than anything I could achieve in my dear old dinghy. To my horror one day when travelling at high speed I struck another boat broadside on. It capsized, the rower was in the water which gladly was quite shallow so when he stood up he towered above me and really gave me 'what for'!

experience after I got accustomed to the moving seat. After a few practices it became clear that this narrow boat could be propelled through the calm waters of a lake at a far higher speed than anything I could achieve in my dear old dinghy. To my horror one day when travelling at high speed I struck another boat broadside on. It capsized, the rower was in the water which gladly was quite shallow so when he stood up he towered above me and really gave me 'what for'!I deserved it! Fortunately the other boat was not damaged - nor was mine. I left the Park, having had a second 'telling-off' from the boat attendant, feeling very ashamed of myself.

The Tower of London, Buckingham Palace, Trafalgar Square with all its pigeons, the National Gallery and its Art treasures, Hyde Park Corner with its speakers of every persuasion. The Mall, the Planetarium and Madame Taussaudes were all visited during my six free weekends, sometimes in the company of another course member. I got to know the London Underground and the London bus routes remarkably well. Yes, it was a thoroughly enjoyable way in which to commence one's army career. Apart from the above mentioned 'sights'. I had the privilege of visiting Westminster Abbey and St. Paul's Cathedral and heard that famous preacher Dick Sheppard in his lovely church of St. Martin's in the Fields. The crypt of the latter was being used as a soldiers' canteen and I benefited from that.

On being promoted to the rank of Sergeant I had, of course, to transfer myself to the Sergeants' Mess where, happily, I was well received. Whether this was due to the fact that I would daily be in contact with the C.O., Second in Command and Adjutant or to their previous knowledge of me in the Q.M. stores I do not know. I like to think it resulted from a general impression of 'wee Alex' - the wee fella from the Highlands - formed during our happy Friday evening training sessions in the T.A.

C) To Selkirk and PiddlehintonWe were not long in Hermiston and Currie before being moved to Selkirk and Galashiels where woollen mills had been requisitioned ('taken over' in ordinary language) for army purposes. Accommodation was of course fairly basic - large barrack - like halls from which the machinery had been removed. The 'other ranks' slept on paliasses (mattresses filled with straw) laid on the floor: Sergeants in smaller units on wooden beds. The large vat in which wool was dyed, when the mill was in operation, was filled with warm water and this provided us with a communal bath capable of accommodating two dozen men at a time in water about 3 feet deep. The C.O. had ordered that all ranks were to have a bath at least once a week so the vat was full every evening; with 550 of an establishment that meant that almost 80 men were washed and bathed every evening all in the same water! No harm came to any of us. The water was changed every day.

Feeding was of the highest standard as the army pre-war ration allowance still applied so we were fed like fighting cocks.

Soon after arrival in Selkirk o

ur old 18 pounder guns were withdrawn, and so we were told, we were the first Regiment to be issued with what was to become recognised as the finest field ordnance in the British Army, namely the 25 pounder. That winter was one of very severe frost in the Borders and the oil in the buffer recuperator systems (the recoil mechanism) of the brand new guns froze solid. The casings were severely cracked, the guns useless! How old Colonel MacLellan fumed, Soon engineers arrived from Woolwich, the guns were removed and almost immediately replaced by new guns in which, we were assured, the oil would not freeze.

ur old 18 pounder guns were withdrawn, and so we were told, we were the first Regiment to be issued with what was to become recognised as the finest field ordnance in the British Army, namely the 25 pounder. That winter was one of very severe frost in the Borders and the oil in the buffer recuperator systems (the recoil mechanism) of the brand new guns froze solid. The casings were severely cracked, the guns useless! How old Colonel MacLellan fumed, Soon engineers arrived from Woolwich, the guns were removed and almost immediately replaced by new guns in which, we were assured, the oil would not freeze.In Selkirk we had our first taste of the warm and generous hospitality which was extended by the local people to soldiers within their midst during the whole of the war. The Churches, Woman's Voluntary Service, British Legion all went to great lengths to entertain ( and feed! ) the troops.

No sooner had January 1940 come to a close than we were ordered to move to a place with the extra-ordinary name of Piddlehinton in Dorset. So on its first long distance move the 78th proceeded, at the prescribed speed of 12-1/2 m.p.h. and with a distance of approximately 100 yards between each vehicle in the convoy, towards this mysterious place. There were 150 vehicles in the Regiment of which 24 were gun-towers. After about five days on the road we completed the 450 mile journey: I had enjoyed it very much sitting as a passenger in a comfortable Hunter wireless truck filled not with wireless sets but with office equipment, files, stationery etc.

Two batteries and Regimental H.Q. were allocated accommodation in halls of various kinds, requisitioned mansion houses and such like in the village of Piddlehinton which we soon discovered was located, yes, on the River Piddle about 5 miles north of Dorchester. The third battery were in Puddletown just a couple of miles down river! The river was in fact no more than a burn.

In Dorset the local drink was Cider and as the pubs did not sell Scottish beer the boys indulged in the cider, encouraged by the locals. Many had to be carried home at night by their mates as the cider was much stronger than any beer to be found in the howffs of Edinburgh. In an effort to control the drinking the C.O. introduced a 10 PM curfew which did not meet universal approval! I still remember typing the order to be placed on all notice boards.

Not being a drinker I used to accompany a few of my Sergeant friends to canteens which had been organised by dear old ladies in church and other halls. They were astonished when we first arrived on the scene that we were not wearing kilts. The locals seemed to be under the impression that all Scotsmen wore the kilt and, moreover, had heather growing between their toes. We spent over three months in Dorset preparing for action. The spring weather was lovely, the apple trees blossoming gloriously. We enjoyed our sojourn in that part of England yet always wondering when the fighting was going to begin: and where. It began so far as the British forces were concerned not by Hitler landings in the UK by sea and air as we had anticipated but when he ordered his forces to move west towards the Atlantic over Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg, and France.

D) The second B.E.F. (British Expeditionary Force)Towards the end of May the Regiment was ordered to move to the Aldershot area. There we were issued with all the extra paraphernalia required by a unit going into action: tons and tons of equipment some of which we had never seen before. At that time the British Expeditionary force was evacuating from Dunkirk and at Aldershot we saw truck after truck arrive with survivors of the B.E.F. some dressed only in their trousers some indeed only in their 'shirts' truly a sorry sight. And here we were fully equipped and 'roaring' to go - but where?

Churchill answered that question when he announced he was sending the second B.E.F. to France to stop Hitler! And so on 5th June 1940 the Fifty-Second (Lowland) Division of which we were part and the 1st Canadians embarked from Southampton and Plymouth. On 12th June we were able to see on the cinema screen in Southampton all 24 of our 25 pdr. guns being lifted individually by derrick on to a large cargo boat! The Second B.E.F. had to turn and flee - for the record I might say that we lost only one vehicle and the guns did not even reach a French port when the Captain of the ship wisely decided to turn back.

Soon the Regiment was directed to East Anglia to defend the shores of old England! The Canadians were down in Kent and together these Divisions were the only fully equipped and manned units of the British Army at that time. We in 78th had only 24 rounds per gun, the normal peace-time holding, while the few soldiers carrying rifles, mainly for guard duty on gun and vehicle parks had six rounds each the same as the officers who carried Smith and Wesson .38 pistols.

E) East Anglia

R.H.Q. was stationed in the small town of Fakenham the people of which took the 'Scottish boys' to their hearts. The three batteries were located in positions, such that one had its guns always 'laid' on Marham aerodrome while the other two were eastwards towards Great Yarmouth and Gorleston those great herring ports.

Accommodation was in bell tents which were erected over a large hole in the ground three feet deep and of the same circumference, or so, as the tent. This was t

o provide shelter against anything other than a direct hit. There was a good deal of bombing by German aircraft but only against aerodromes. We were told that the spire of Ely Cathedral and its copper roof were being used by the enemy as navigational guides and no doubt that was the case for no attempt was made to bomb Ely.

o provide shelter against anything other than a direct hit. There was a good deal of bombing by German aircraft but only against aerodromes. We were told that the spire of Ely Cathedral and its copper roof were being used by the enemy as navigational guides and no doubt that was the case for no attempt was made to bomb Ely.At this stage our Divisional Medical Officers were finding more and more men inflicted with venereal disease and this created more worry among the Commanding Officers than a German landing would have done. What was to be done? In the end it was decided to ask the Reverend Roland Selby Wright, Minister of the Canongate Kirk in Edinburgh and Warden of the famous Canongate Boys Club to use his influence with the men of the Division. And so it was that the Cathedral at Kings Lynn saw every officer and other rank of the Division in relays - fill its pews and choir stalls while they listened to R.S.B. preach a sermon on true love. He had a most wonderful way of getting his message home to men: we were reminded of the wives and mothers, sisters, fathers, brothers, grannies and granddads at home in Edinburgh and of the heart-breaking effect news of V.D. in their loved one far from home would have. I don't suppose his appeal for celibacy was answered by all his hearers but the doctors saw an immediate drop in the number of cases and never again did the same problem arise.

In the Division we also had as Senior Padre the Rev. Joseph Gray M.A.,T.D. (later to marry Wilma and myself) and Rev Leonard Small (of St. Cuthberts). With their support I was able to obtain large quantities of C of S. Huts Notepaper and envelopes from 121 George Street, Edinburgh and to distribute these among the troops as an encouragement to write home regularly. All the officers became involved in my 'scheme' and this certainly helped tremendously in maintaining morale over a number of years.

On one of the occasions when the Adjutant had me with him down at the Coast several bodies of Germans were washed ashore, probably air crew who had been shot down. This resulted in a rumour that the Germans 'had tried to land and been beaten back' as one paper had it.

However the C.O. had news from the War office that the Germans were mustering barges and similar craft in Holland and invasion was to be expected soon. Guards at all posts were doubled and we all lived in great expectation.

However, there nearly was a mutiny in the Division! We had been issued for several weeks with nothing but tinned fish, herring, pilchards, salmon and tuna, for breakfast, dinner and tea! What a blessing the local ladies had set up their canteens and that we had access to 'good food' like sausage and mash, beans on toast, pork pies and so on. So bad was the situation that each Regiment was visited by no less a person that the King accompanied by our G.O.C. General Ritchie. The latter told each parade that the government apologised for the daily offerings of tinned fish but, he said, food intended for the United Kingdom from Canada and U.S.A. was being lost at sea every day. What we were receiving had come from government reserves. This did nothing to assuage the hunger of the young men who had until recently been fed nothing but the best.

Soon after this we were moved again this time to Scotland!

F) Back to Scotland

Our move back to Scotland included a firing camp at Otterburn in the Borders which lasted almost two weeks. This really allowed the boys on the guns to let off steam and the rest of us to see them in action firing live ammunition. It was a pleasant break in good weather. Our destination was Falkirk where we were accommodated in halls of all sorts . R.H.Q. was in an office right in the centre of Falkirk. One of those whose livelihood had been taken away from him was a Mr Jimmy Turpie a dancing instructor who told me, he had been a stoker in the Navy in World War I. He kept coming to see me about the possibility of allowing him to resume dancing classes in one or more of the halls which he had previously rented. There was nothing I could do about that but I was able to help him sort out his Income Tax affairs which were in a shocking state. In return he and his good lady, Mary extended kind hospitality to me and Jimmy even taught me how to do the quick-step, fox-trot, waltz and tango! I was never very good at these but Jimmy must have had an ulterior motive - or maybe it was Mary. Their daughter Jean was engaged to a Falkirk lad who played for the local football team but Jimmy entered me as her partner for a competition dance at the local ice-rink. To my utter astonishment we won first place in the quick step and slow fox-trot! Great rejoicing in the Turpie family and much leg-pulling in the Sergeants Mess! When I heard soon after this that the engagement was to be broken off I had to be quite firm and told Mother and Daughter that I was not in the slightest bit interested. So the engagement ran the usual course and Jean and her fiancee married. (He became an Electrical Engineer and worked in the Electricity Supply Industry as I was to do).

Actually the people of Falkirk were most kind to the troops providing all sorts of entertainment. At the ice rink one quarter of the skating area had been boarded over and fenced off from the skaters. The local W.V.S. were as always, quite wonderful. During this period I acquired a pair of skating boots and had instruction from some of my colleagues who could already skate. But I never did become an expert!

We were in Falkirk for only three months when the Regiment was moved to Dunblane and Auchterarder. From here it was easy to gain access to the firing ranges on Shefiffmuir. I have no recollection of anything exciting happening in Dunblane except perhaps that we were selected to participate in a service broadcast from St. Blanes Church at which Ronald Selby Wright preached an inspiring sermon and I was introduced to a prominent person in the B.B.C (whose name I've forgotten) who suggested I join his organisation as a news reader on the Empire service when war was ended. (We still had an Empire at that time!) He would personally recommend me because of my Inverness accent. But I did not take up that offer.

The next move was to Haddington in East Lothian where I became friendly with the late Rev. Robin Mitchell minister of the church beside the Regimental office. He was a great outdoor man and an expert on the flora and fauna of the area,. It was with him while we were fishing on the River Tyne one evening that I saw, for the only time, the death dance of the flies. Literally millions of flies gathered along the still waters of the river in the shape of a cone towering perhaps twenty or thirty foot high. The noise of humming as they rose into the air was awesome: the vertical climb lasted for about five minutes and then all at once the whole cone collapsed and fell into the Tyne. A truly moving experience which I have never forgotten. Robin and his wife were most kind to me all the time I was in Haddington. One of my clerks was the son of a Minister who loved to play the organ so he was appointed organist for all church parades -although he claimed to be an atheist. Jimmy Milne was his name and before the war he had become famous by marrying while still under the age of 25 contrary to the regulations governing employees of the Commercial Bank for which he worked. He was dismissed but appealed to the Court of Session on the grounds that the regulations were 'Contra libertatem matrimonii' The law of Scotland regarded as illegal any restraints put on marriage - it probably still does; I hope so anyway. I used to give him permission on a Saturday evening to leave his quarters above the office in order to practice 'for tomorrow'. Little did he know that five or six of us including the Adjutant and Second-in-Command crept into the back seat of the church while Jimmy sat in candlelight at the organ playing beautiful pieces of music from the classics, Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Handel among them. For an hour we would sit enchanted by the wonderful music and then creep silently out into the night. If the organist had known he would have risen and left. Then one night the noise of aircraft filled the skies: enemy bombers on their way to Clydebank and Gourock but we did not know that. The anti-aircraft guns in the district were 'pooping off' all around Haddington while searchlights pierced

the darkness. One bomber was hit and crash landed in a field outside the town but not before it had dropped five bombs all of which hit Military targets - his good luck and not good judgement. The quarter-masters store in a tenement in the centre of Haddington had a direct hit and was set ablaze. My friends Joe and Bob managed to escape by 'shinning' down a drain pipe. Across the street an unexploded bomb fell through the roof of a tenement and landed at the foot of the stairwell. In that tenement another of my boys - the most gentle of souls - had rented a room and kitchen for himself and his bride of a few days. He picked up the 50 kg bomb and carried it out the back door, across the back green and dropped it over the boundary wall - all in order that his lovely wife should not be killed. The three other bombs landed in the main car park and the gun park and although they exploded no damage was done.

the darkness. One bomber was hit and crash landed in a field outside the town but not before it had dropped five bombs all of which hit Military targets - his good luck and not good judgement. The quarter-masters store in a tenement in the centre of Haddington had a direct hit and was set ablaze. My friends Joe and Bob managed to escape by 'shinning' down a drain pipe. Across the street an unexploded bomb fell through the roof of a tenement and landed at the foot of the stairwell. In that tenement another of my boys - the most gentle of souls - had rented a room and kitchen for himself and his bride of a few days. He picked up the 50 kg bomb and carried it out the back door, across the back green and dropped it over the boundary wall - all in order that his lovely wife should not be killed. The three other bombs landed in the main car park and the gun park and although they exploded no damage was done.When the C.O. heard what Gunner Bartlett had done with the unexploded bomb he nearly had a fit! But while he contemplated a court martial decided in the end simply to reprimand Bartlett. After the C.O. had explained how dangerous and therefore wrong it was to handle an unexploded bomb I remember Bartlett saying in his quiet way "and what would you have done, Sir, if your wife had been similarly placed?" The reprimand was merely a warning 'not to do the same again'!

Our C.O. Colonel MacLellan was moved and replaced by one who had been a Gunnery Officer at Larkhill, near Salisbury - the school of gunnery. He was a real fire brand! No sooner had he arrived than he was out inspecting every troop, every battery and, almost, every gun. It was evident that a disciplinarian had arrived as I typed order after order about every conceivable activity to go out to Battery Commanders. One of the first was that every member of the Regiment regardless of rank would parade on the nearest gun park at 6. am for physical 'jerks' under a P.T. instructor and whatever the weather. A foretaste of Monty's regime! You can probably imagine how clerks and cooks unaccustomed as they were to daily drills or parades reacted. But in the Army orders are orders. The P.T. Instructor for Regimental H.Q. was no less a person than the C.O. dressed in shorts and singlet. He had us hard at it for 30 minutes each morning before we were allowed to wash and shower at the out door toilet arrangements - cold water was freely available from a tap set above a metal wash hand basin.

Before the end of the first week he asked me to come in and bring my personal file. I knew not what was in store. After reading through it he demanded to know why I had not gone for the officer's training course offered in 1939 as I was just wasting my talents in this present job! My explanation was, of course accepted but he told me that he personally was going to arrange for me to go O.C.T.U. (Office Cadet Training Unit) as soon as possible. Meantime I was to go out to 181 Battery as a gun sergeant, learn all I could about the 25 pdr and ballistics and generally become a 'real gunner' to justify, as he put it the wearing of a gun on my arms! So off I went and did as the C.O. had told me to do. The gun itself and every part of it had to be mastered as also the trailer, in which 24 rounds of ammunition were carried, and the GUY gun-towing vehicle which not only pulled the trailer and gun but carried the gun crew of six including myself. Up until now the army had not let me loose among things mechanical and I revelled in this new found interest. There were handbooks to study, gun drill books to read and absorb and a detailed maintenance manual in relation to the Guy. I determined that before ever going to O.C.T.U. I would be a 'real gunner' as the C.O. had ordered and with the co-operation of my crew of five men and my fellow sergeants I like to think I was. We had several opportunities of firing live ammunition at Otterburn and Sheriffmuir. It was at the latter that my hearing was damaged. There was mist on the target area in the hills, the range was 10,000 yards and to reach this the layer (known as No. 3 on the gun) elevated the barrel to the required angle, I realised it was now fowling the camouflage net and proceeded to unlace the net to allow free movement of the barrel when the gun fired, the order to fire came as a shout from the Command Post and my layer without waiting for me to return to the No.1's position at the trail of the gun and then shout 'Fire', pulled the trigger. My head was about six inches from the barrel as the shell roared away into the sky. The blast knocked me out and when I came to I was at the Command Post, being cared for by a First Aider, with blood coming from each ear. Soon I was in Stirling Infirmary but was discharged that evening. For several months I suffered pains in my ears but when the call came for me to proceed to O.C.T.U. the doctor declared me A1 and off I went.

G) O.C.T.U. (Officer Cadet Training Unit)

Early in March 1942 I arrived at the railway station at Catterick in York-shire along with a number of other Sergeants, Bombadiers and Lance/Bombadiers all destined for six months at 121 O.C.T.U. One of the Sunday newspapers had given it the name of the 'Hi-di-Ho, Ho-di-ho' O.C.T.U. where 'they made you or broke you'. Certainly it turned out to be the toughest six months I have ever known.

On arrival at the barracks - a real army barracks not unlike Fort George - our uniform was taken from us and were issued with new battle dress uniform (with No badges of rank) and a white cotton band to be worn round our 'forage' caps - this was the distinguishing badge of an officer cadet.

Of the 49 Cadets in the 'intake' 24 were from Oxford and Cambridge Universities, and 25 who had already been soldiers. Sleeping accommodation was in rooms for six or eight men with two tier bunk beds and polished wooden floors. For the first four weeks we had infantry training and in the gym the P. T. instructors endeavoured to make us gymnasts. Reveille was at 6.30 am with half and hour for ablutions in the barracks before 'falling in' on the parade ground for P.T. We were certainly ready for breakfast at 8 am! Before going out again for our first parade at 9 am we had to ensure that all our kit and blankets were made up in the approved regular army fashion. Before leaving the room we had to polish the floor so that it shone like a mirror with never the mark of an army boot on it. This was achieved with a heavy polisher on which, in our room I, as the smallest occupant, used to sit while one of my comrades pushed the polisher up and down over the floor retreating all the time towards the entrance. This procedure ensured that when the Sergeant Major inspected our room he found the place spotless. If he did not then the punishment was that all the occupants of the room concerned had to endure half an hour of drill on the parade ground after supper.

The office in charge of our squad of 45 Cadets was one Captain Garron-Williams (whose father we were told was a Brigadier on Monty's staff). He was known to all as 'Garbage Bill'. He was a real snob disliked not only by the Cadets who had been in uniform before 121 but the student cadets from 'Oxbridge' who themselves were regarded by others as being rather 'toffee nosed'. Perhaps because I was the smallest in the squad Garbage Bill took a special dislike to me. Because I was so small, because I was only a fisherman's son, (his words) because my father had been only a deck-hand in the Great War he assured me, one day, that I hadn't a hope of being commissioned. Of course I had no means of responding for to have done so would no doubt have seen me on a charge for 'speaking back' to an officer.

Ah well, we marched and counter marched, slow march and quick march, we ran for miles over the Yorkshire dales, crossed rivers by means of hand-hold ropes, fired rifles, bren guns and .38 pistols, endured a battle course in which we ran for miles, marched for miles, climbed trees, slid down ropes, vaulted over fences and ended up at the firing range: here we had to loose off six rounds at the distant target with arms and hands that were anything but steady. And all to prove that we could be gunner officers.

Towards the end of the fourth week we were on the 30 yard range one day when 'Garbage Bill' challenged anyone in the squad to 'take him on'. A fellow Scot, Shug MacGowan a Sergeant in the 79th Field Regiment of Greenock, spoke up! 'Cadet Cameron will take you on, Sir'. I was horrified for Shug was a good friend of mine. However I agreed. G.B. offered a choice of firearms but brought out a beautifu l leather bound, velvet lined case containing two German Mausers and said he would prefer to use them. I had never seen anything like those pearl-handled pistols except in the museum in Edinburgh but as soon as I held one in my right hand I knew it was perfect for me. After all my Dad, who was a crackshot in World War I, had taught me to shoot. G.B. set up two targets the size of Swan Vestas' match boxes - at 30 yards they looked like bulls eyes and then tossed a penny to decide who should go first. I won the toss but when G.B said 'Oh well, that means you go first Cameron'. I replied that as in a game of cricket it was my privilege to let him 'bat' first. He did and put 5 bullets in the target. The good Lord was with me that day steadying my hand - yes, all six went through the target. G.B. was overcome - he was the crack shot of his unit - and this diminutive Scot had beaten him. The applause from the squad was heart warming but so also was the congratulations bestowed on me by G.B. He drove me to the Officer's Mess where the C.O. and second-in-Command were having tea, introduced me, told them what had happened and invited me to have tea with him. After that I never looked back!

l leather bound, velvet lined case containing two German Mausers and said he would prefer to use them. I had never seen anything like those pearl-handled pistols except in the museum in Edinburgh but as soon as I held one in my right hand I knew it was perfect for me. After all my Dad, who was a crackshot in World War I, had taught me to shoot. G.B. set up two targets the size of Swan Vestas' match boxes - at 30 yards they looked like bulls eyes and then tossed a penny to decide who should go first. I won the toss but when G.B said 'Oh well, that means you go first Cameron'. I replied that as in a game of cricket it was my privilege to let him 'bat' first. He did and put 5 bullets in the target. The good Lord was with me that day steadying my hand - yes, all six went through the target. G.B. was overcome - he was the crack shot of his unit - and this diminutive Scot had beaten him. The applause from the squad was heart warming but so also was the congratulations bestowed on me by G.B. He drove me to the Officer's Mess where the C.O. and second-in-Command were having tea, introduced me, told them what had happened and invited me to have tea with him. After that I never looked back!

At the end of the week 25 Cadets were rejected leaving only 24 to continue into gunnery training. How many hearts were broken by the Hi-di-hi, hi-di-ho OCTU! No wonder the Sunday newspapers were so critical.

Being already a 'real' gunner I loved the remaining five months of training hard work as it was. I passed my driving test on a 3 ton truck laden with 3 tons of ammunition. These were the days of square cut gear boxes. One commenced the test at the foot of the steepest hill in Richmond and was required to stop and take off (without moving back even one inch!) four times. Anyone who failed here was not allowed to proceed further. Gladly I managed all the other manoeuvres and received my driving license.

By the end of the fifth month 20 of the squad were informed that they would be commissioned and could now proceed to order uniform and camp gear etc. In Richmond, not surprisingly, there were two well known services tailors. It was a thrilling experience for us cadets to be measured for officers' uniforms, to select shoes, Sam Browne belt and cap. We all had three fittings and paid over our £32 allowance (granted by the government) - this covered only the service dress so we had to pay for the rest. In addition I elected to have the allowance of £18 for my camp bed, valise (which held the issue of three blankets) and some other items rather than the Army issue, the bed of which was far too cumbersome. My safari camp bed is still in occasional use (by grand children) after 53 years!

On the final day at Catterick we had to dress as officers in our new uniform for inspection by the Commanding Officer who naturally addressed us in suitably glowing terms. Thereafter the Adjutant read out the extract from the London Gazette in which our names appeared and came round handing out rail passes and instructions regarding routes to the Regiments in which we were now to serve. What I did not know was that my old C.O. had requested that I be posted back to the 78th Field: this was unheard of in the army but here I was detailed to proceed to Old Meldrum. Fortunately we were all given seven days leave so I was able to go North to see my dear Mum an Dad and friends in the old village. Little did I realise how much pleasure my commission would give to my parents: I suppose it was something they may have hoped for their son. Our Minister Rvd. Campbell Macleroy and his good lady had me visit the Manse for tea and presented me with the 'Little Bible' which is still in use: a complete bible without all the irrelevancies!

suitably glowing terms. Thereafter the Adjutant read out the extract from the London Gazette in which our names appeared and came round handing out rail passes and instructions regarding routes to the Regiments in which we were now to serve. What I did not know was that my old C.O. had requested that I be posted back to the 78th Field: this was unheard of in the army but here I was detailed to proceed to Old Meldrum. Fortunately we were all given seven days leave so I was able to go North to see my dear Mum an Dad and friends in the old village. Little did I realise how much pleasure my commission would give to my parents: I suppose it was something they may have hoped for their son. Our Minister Rvd. Campbell Macleroy and his good lady had me visit the Manse for tea and presented me with the 'Little Bible' which is still in use: a complete bible without all the irrelevancies!

As a commissioning present my Mum and Dad presented me with a pair of leather gloves and a leather covered swagger cane. A magnificent present it was and I was so proud of it. Sadly two years later I lost both gloves and cane by leaving them behind after crossing London in a taxi from one station to another. To this day I regret that loss.

H) 182 Field Regiment R.A.From Fort George station at Ardersier I travelled by train to Inverurie where an Army truck was waiting to transport me the five miles to Old Meldrum. To my surprise I learned that the 78th Field Regiment had been broken up and was now on its way to the Middle East. One half of the Regiment had joined one half of the 79th Field and together were known as the 78th. The remaining half of my 'old' unit had been augmented by an intake of gunners from various other units and the combination was known as the 182 Field Regiment R.A. Happily the old C.O. and the Adjutant who had both wanted me back were still there and I was welcomed like the proverbial long lost brother. The R.S.M. who had drilled me at Murrayfield had also been 'left behind' when the 78th had left. The split had come a few weeks only before I left OCTU, but was so secret that my posting had been shown as being to the 78th. However all was soon cleared up and I was glad to be among so many well kent faces. To begin with the relationship between the former Sergeant and those who knew him as 'wee Alex' was somewhat delicate but not for long.