Chapter XII

Edinburgh

a) Arrival

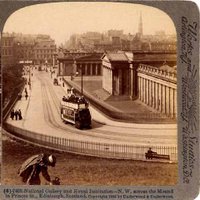

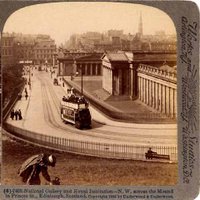

On arriving at Princes Street Station in Edinburgh I proceeded with my bowler hat on my head (nowhere else to put it) my suitcase of clothes in my right hand, and sports bag (containing mainly cricket and tennis gear) in the other to climb towards Princes Street and the No. 9 tram which would take me to Bruntsfield where my landlady Mrs Jess MacKenzie lived. The wind in the Waverly steps was gusting at least force six and as I was almost at the top the wind took off my bowler hat and carried it over trams, cars and the Woolworth building (2 storey high) out of my sight to an unknown destination. I made no effort to retrieve it - how could I encumbered with two cases and knowing nothing of the geography of Edinburgh?

Bruntsfield where my landlady Mrs Jess MacKenzie lived. The wind in the Waverly steps was gusting at least force six and as I was almost at the top the wind took off my bowler hat and carried it over trams, cars and the Woolworth building (2 storey high) out of my sight to an unknown destination. I made no effort to retrieve it - how could I encumbered with two cases and knowing nothing of the geography of Edinburgh?

Having stepped inside the first No. 9 tram that came along I sat downstairs, paid my fair of 1 penny and admired the wonders of Princes Street marvelling at the large numbers of folk who were walking on the pavements and in gardens. What did they all do for a living? The tram turned left at St. John's Church at the west end of Princes Street and proceeded up Lothian Road. The conductor told me where to get off for Bruntsfield Avenue. When I reached No. 10 it was to find that I had to pull a brass knob marked 'Mackenzie' - thereupon the main or front door opened (of its own accord?) and I entered. High above me I heard the welcoming voice of her who was to become my second mother - Jess Mackenzie. To reach her flat one had to climb 78 steps - the highest I had ever been!

Immediately I was made to feel at home. Her daughter Isobel 14 years old and son Ian 12 were of course known to me as they used to come up to Ardersier to holiday with their grandparents Mrs MacKenzie's father and mother. Because there were two other lodgers in the four bedroom flat the front or sitting room had been allotted to the new lodger. This was the biggest room in the flat with fine furniture including a bed settee for the lodger. Yes. it was very comfortable. The other two lodgers one a Civil Servant (name of Sibbald) and the other a hair dresser (Jean was her name) had chosen to have their meals in their respective rooms but I decided I would dine with the family in the kitchen. And so commenced a year of hard work and great happiness.

I soon became the chief dish dryer! Mrs MacKenzie was a fine cook and baked scones, cakes, cream sponges to make one's mouth water. Sibbald and Jean had their meals taken in to them on trays. Ian did one, Isabel the other. The bathroom was allocated on a strict time basis: Sibbald at 7.30 am, Jean at 7.45 am and myself at 8.00 am. During the whole year that I lived in that home I never saw once either of the other lodgers. Strange but true. Their names were constantly mentioned, naturally, as they formed part of the menage but they truly 'kept themselves to themselves'. For board and lodging I had to pay £1-5/-(One pound and five shillings) per week and 2/6d (half a crown) for laundry. Apart from my bursary of £30 my salary with the Edinburgh firm was to be 10/- (ten shillings) per week. Most of the bursary money would be taken up with matriculation and class and examination fees in addition to which the prescribed text books, note books and such like would have to be paid for? What faith we had in those days!

b) Palmerston Place ChurchI had arrived on a Saturday and Mrs Mackenzie invited me to attend her church which was nearby. I did this but found the minister very dull after my beloved Mr Maceleroy. So I was told that the place for me was Palmerston Place Church where the Minister was Rev. William C. MacDonald M.A. and that I should go there that evening. On arrival at this large church in the West End I decided to go up into the balcony. At the top of the winding stair case a red haired tall young man of my own age invited me to help him to hand out the hymn books of which there seemed to be hundreds piled up against the walls. Never had I seen so many people, mostly of student age enter the portals of a church. How they were seated I had no idea but when the number of hymn books had diminished to a dozen or so Bill Peat (by this time I knew his name!) told me we had better go inside and 'pack them in'. I had no idea what I was in for but there as we entered was a sea of faces before me! There was little option but to do as Bill had asked me and by the time we ourselves had to sit down there was room only on the balcony steps. What an uplifting experience that was. As I had thought most of the congregation that evening, and as I was to find out later every Sunday evening, the church was packed with students eager to hear Willie MacDonald preach. The singing 'raised the roof' and during the sermon you could hear the proverbial pin drop. Remember we were living in the age when the German Jack Boot was tramping across Europe, Hitler was shouting his obscenities over the radio, Jewish people were being terrorised and many arrived in Britain telling of the obscenities already being perpetrated by the Nazis. Willie MacDonald had been a student of that great theologian Karl Barth in Switzerland. Barth had held Professorship at Gottigen and Bonn and his influence was such that he changed the whole outlook of Protestant theology on the Continent. He stressed the absolute difference between God and man, man's inherent inability to solve his own problems and his complete dependence on revelation and grace offered to man in the person of Jesus Christ. This was what Willie preached in sermon after sermon and in the most acceptable manner. No wonder young folk came from all over Edinburgh to hear his sermons. Having joined the Church in Ardersier I decided that evening to 'transfer my lines to Palmerston Place and soon was a member there. I also joined the young Men's Guild in which we had 70 or so members - at that time all pacifists! Meetings largely took the form of debates or talks by visiting 'experts' or members themselves. I had the privilege of reading a paper on the subject of Crime and Punishment - reading it some 50 years later I found that my views had changed little although my style of presentation had. Another subject on which I made the motion and therefore spoke at length was the 'Iniquitous Disparity between the income levels of miners and fishermen and the professional classes!' I remember arguing that Miners and Fisherman should have a guaranteed wage of £1,000 per annum! The motion was carried. One of our members was the Rev Stanley Mair the Assistant Minister. He had a voice like a trumpet and it was a joy to listen to him making a point. Some time after this a number of us persuaded him to speak at the Mound when in those days speakers on all manner of subjects from socialism to atheism 'spouted forth' on a Sunday evening. We persuaded the Church of Scotland to let us have their soap box which was agreed on condition that it was returned to St. Cuthbert's Church after use. When we arrived the Minister for that evening seemed to be glad to hand over to Stanley. No wonder - the noise of speakers shouting was horrendous. Standing mounted on the box, he took off his jacket, rolled up his sleeves, took off his red tie and literally 'bellowed' at the crowds gathered round the other speakers. So loud was his voice and so compelling his words that very soon he was surrounded by folk who had even given up listening to the others at the Mound: Even the Salvation Army Band ceased playing in order to hear this - new voice. From then on Stanley Mair's oratory could be heard at the Mound regularly, indeed he became one of the 'star' speakers on a Sunday evening until the forthcoming conflict saw him like the rest of us away on active service.

out the hymn books of which there seemed to be hundreds piled up against the walls. Never had I seen so many people, mostly of student age enter the portals of a church. How they were seated I had no idea but when the number of hymn books had diminished to a dozen or so Bill Peat (by this time I knew his name!) told me we had better go inside and 'pack them in'. I had no idea what I was in for but there as we entered was a sea of faces before me! There was little option but to do as Bill had asked me and by the time we ourselves had to sit down there was room only on the balcony steps. What an uplifting experience that was. As I had thought most of the congregation that evening, and as I was to find out later every Sunday evening, the church was packed with students eager to hear Willie MacDonald preach. The singing 'raised the roof' and during the sermon you could hear the proverbial pin drop. Remember we were living in the age when the German Jack Boot was tramping across Europe, Hitler was shouting his obscenities over the radio, Jewish people were being terrorised and many arrived in Britain telling of the obscenities already being perpetrated by the Nazis. Willie MacDonald had been a student of that great theologian Karl Barth in Switzerland. Barth had held Professorship at Gottigen and Bonn and his influence was such that he changed the whole outlook of Protestant theology on the Continent. He stressed the absolute difference between God and man, man's inherent inability to solve his own problems and his complete dependence on revelation and grace offered to man in the person of Jesus Christ. This was what Willie preached in sermon after sermon and in the most acceptable manner. No wonder young folk came from all over Edinburgh to hear his sermons. Having joined the Church in Ardersier I decided that evening to 'transfer my lines to Palmerston Place and soon was a member there. I also joined the young Men's Guild in which we had 70 or so members - at that time all pacifists! Meetings largely took the form of debates or talks by visiting 'experts' or members themselves. I had the privilege of reading a paper on the subject of Crime and Punishment - reading it some 50 years later I found that my views had changed little although my style of presentation had. Another subject on which I made the motion and therefore spoke at length was the 'Iniquitous Disparity between the income levels of miners and fishermen and the professional classes!' I remember arguing that Miners and Fisherman should have a guaranteed wage of £1,000 per annum! The motion was carried. One of our members was the Rev Stanley Mair the Assistant Minister. He had a voice like a trumpet and it was a joy to listen to him making a point. Some time after this a number of us persuaded him to speak at the Mound when in those days speakers on all manner of subjects from socialism to atheism 'spouted forth' on a Sunday evening. We persuaded the Church of Scotland to let us have their soap box which was agreed on condition that it was returned to St. Cuthbert's Church after use. When we arrived the Minister for that evening seemed to be glad to hand over to Stanley. No wonder - the noise of speakers shouting was horrendous. Standing mounted on the box, he took off his jacket, rolled up his sleeves, took off his red tie and literally 'bellowed' at the crowds gathered round the other speakers. So loud was his voice and so compelling his words that very soon he was surrounded by folk who had even given up listening to the others at the Mound: Even the Salvation Army Band ceased playing in order to hear this - new voice. From then on Stanley Mair's oratory could be heard at the Mound regularly, indeed he became one of the 'star' speakers on a Sunday evening until the forthcoming conflict saw him like the rest of us away on active service.

c) Kinimont & Maxwell, W.S.

On the Monday following my arrival in Edinburgh I reported to my new office at No. 11 Coats Crescent, Edinburgh. Mrs MacKenzie had told me how to get there and as it was quite near Palmerston Place I had a preview on the Sunday evening noting carefully that it would take me 20 minutes to walk along Shandwick Place and up Lothain Road, Earl Grey street and Bruntsfield Road to my lodgings. Downhill would be achieved in less time. So, as the tram fare to the West End was one penny I decided to walk to the office. I was wearing my three guinea suit when I arrived and was led to the office of Robert W. Martin, W.S. the junior partner. He gave me a warm welcome and asked the Managing Clerk a comparatively young man, Duncan Livingstone MacDonald, Solicitor, to come and meet the new apprentice. This he did very warmly and then took me to meet the Cashier, her staff and then the typists. Eventually I was guided into the apprentices' room. There were three others and to my great embarrassment all were wearing tatty old jackets and flannel trousers! You can imagine how I felt all dressed up as I was in my fine new suit. At lunch time I walked home and changed into informal clothes, even so my new tweed jacket and flannels 'stood out a mile' compared to the others with whom I was to work. The Dickensian desk at which we sat on high stools made me wish I was back at my 'proper' desk in Inverness. However one can get accustomed to most things in life and so it was here.

I was allotted work relating to several Executries and Trusts and was taken aback by the values. In Inverness we had dealt with tens of thousands with the occasional six figure estates but here all I had before me were for six figure sums. The K & M clients must be very wealthy! As indeed most of them were. Two of the other apprentices, Ramsay (he was always addressed by his surname) Hector Ross the son of a Hill Street publican, were in their third year of the B.L. degree while Bob Coutts from Kinross was in his second year. They all proved to be very helpful to me and Bob became a firm friend outwith office hours. The Cashier Miss Hamilton was, to me, an old lady who ruled the cash room and the typists also with the proverbial rod of iron.

The senior partner of the firm was Francis Celement Nimmo Smith, W.S. who used to arrive in a chauffeur driven Rolls Royce at 10.00 am was then enclosed with Bertie (as he was affectionately called) Martin and sometimes also D.L.M. the Managing Clerk until 11.00 am or 11.30 am going, as I was told, going over the mail. Soon after his arrival the office caretaker Mrs Mackenzie a lady from Lochiver used to ascend from her basement dwelling bearing a silver tray on which she carried a silver tea service and the best china. This she took in to the boss's room. I may say it was from our dear old Mrs Mackenzie that I first tasted china tea!

Soon after 11.00 am F.C.N.S. (as we called him) departed in his limousine for lunch at a golf club at a place called 'Gillane'. I was soon to discover that what the map told me was 'Gullane', in Edinburgh was pronounced in a more genteel fashion! F.C.N.S. never once in the time I was with K and M appeared in the office except to 'go over the mail' as mentioned above.

After I had been in Edinburgh almost one month D.L.M. told me that the chief wanted to see me. When I entered his room he welcomed me to the firm and wished me well. He already knew all about me and my back ground and was particularly interested in the fact that I had already joined a cricket club and a tennis club in Edinburgh. He was delighted to hear that not only had I seen the Australians play the Northern Counties in Forres but had 'caught out' Don Bradman. In reply to one question I told him of my bursary and the salary being paid by his firm.

He asked me how I was going to survive in Edinburgh when my outlays so far exceeded my income. I remember telling him that my parents were people of great faith! He knew of course all about the sad economic state of the fishing industry at that time. (I already knew he had shares in two fish processing companies!) 'Now' he said 'you are to tell Miss Hamilton to pay you twenty-five shillings a week in addition to your salary and that will pay for your digs'. I thanked him most humbly and on leaving his room went straight to Miss Hamilton in her glass compartment to tell her my good news. She almost had a heart attack at my effrontery. When I assured her I really was telling the truth she rushed into Nimmo's room but soon returned. She said I was a very lucky young man, I was to tell nobody of the senior partner's generosity, as I was now to be the highest paid of all the employees except the Managing Clerk, D.L.M. And so I had 10 shillings per week from which had to be deducted ten pence as my contribution to the Inverness County Benefit Society ( a sort of fore runner of the N.H.S.) leaving me with nine shillings and two pence from which my laundry bill was paid. In other words my net income for the rest of my pre-war days with K & M was 6/8d (six shillings and eight pence per week). Remember a bar of chocolate cost only tuppence and the tram from Waverley to my digs in Bruntsfield cost one penny.

With K & M my work load extended to Income Tax in which I found myself being regarded as an expert (all thanks to the Civil servants in the Tax office at 42 Union Street, Inverness and the School of Accountancy), some minor conveyancing for clients buying bungalows for £300 to £500, valuation of investment portfolios for our many wealthy clients and the occasional Court of Session action. Ramsay and Hector were given the job of introducing me to Parliament House and the Court procedures followed there. I do not remember one small debt summons or any other action in the Sheriff Court: our clients were 'above that sort of thing!;.

d) Edinburgh University (Pre war)Early in October 1939 I proceeded to the University -twenty five minutes walk from my digs, across the Meadows to George IV bridge, down Chambers Street and right into 'the Bridges' where the first opening on the right gave access to the beloved 'Old Quad'. I obtained my matriculation card and enrolled for the classes in Civil (otherwise Roman) Law and Jurisprudence ('science of law' no less) each being three term courses and put myself down for the class in Forensic Medicine which would commence in January and last for only two terms. Now I was all set to study law! The office, of course, recognised that Apprentices were also students who required time off to attend classes. Civil Law classes commenced at 9.00 am when an old (very old) Professor Mackintosh sat at a desk and read notes which he had first written when appointed to the Chair forty years previously! We were expected to take notes and if my writing is bad you can blame these classes. The lecture room was laid out with pews and book boards in terrace format the back row being, I'm sure, ten feet above the Professor! Because of my stature I could not hope to lean my note book on the book board provided, it was so high in relation to the seat that I could not possibly write and chose to sit on the steps with note book supported on my knees scribbling away like mad while the Prof. read his notes at a speed of about 250 words per minute. At the end of the first week a number of us asked the old boy if we could have copies of his lectures or even a précis issued to us. The answer was that this had never been done before and he was not going to start now!

Like most of my fellow students I had been able to purchase, in James Thin's second hand book shop in Chambers Street, copies of Justinian's Institutes as well as those of Gaius at a price of 1/3d each. They were no longer being published yet they were prescribed reading. These books were set out in columnar form with the Latin text on the left and English translation on the right - thank goodness. Accordingly while at exam time one could readily answer questions in English one could also translate passages from Latin into English - assuming always that one had done the necessary work.

Sadly Professor Mackintosh died early in the third term and his place was taken by the Dean of the Faculty, Professor Matthew Fisher. He simply took over his predecessor's notes and read them to us! He also decided that the degree exams would 'in the circumstances', be deferred until September. That was to give us more time for study or so he said!

For jurisprudence the text book was also available in James Thin's at a cost of one shilling. Classes commenced at 1.30 p.m. and continued for no more than 40 minutes - long enough for most of us who regarded the subject as somewhat esoteric or nebulous and of no use whatsoever in the hurly burly of the Sheriff Court or so far as any of us could judge at that stage in our careers, the Court of Session. However it was a required subject for degree purposes. Many a weary evening I spent in the George IV Library trying to assimilate the mysteries of jurisprudence. I remember the professor (I think Guthrie who may have become Lord Guthrie) telling even he was not sure why the subject was mandatory - he had wondered that when a student too-his job was to lecture on it!.

The classes in Forensic Medicine (when they commenced in January 1939) were held in the medical faculty premises and were attended by hoards of medical students and a fair number of law students. Classes commenced at 4.30 p.m. and usually lasted for one hour. On a number of occasions classes were convened earlier in the day or even on a Saturday morning. These were always 'practical' in the sense that there in the middle of the room on the table lay the body of someone who had very recently been murdered in some devilishly foul manner or poisoned over a long or short period of time.

I omit the gruesome details of these post mortems. Suffice it to say that while the medical students would crowd around the body to see closely what the pathologist was up to many of the law students either passed out or had to leave the room. Perhaps it was good experience for what many had to experience during the war.

Professor Sidney Smith had become well known at the time of the notorious 'Buck Ruxton' murder trial and he delighted in showing us 'samples' in jars of formalin. At one time he had been in the service of the Egyptian government and had managed to solve some mysterious murders. How he delighted in relating the sordid details!

You will remember that a 20 minute walk took me from my digs to the o ffice, a 25 minute walk took me to the old Quad and surprisingly one could walk from the Old Quad to Coates Crescent in 20 minutes . However it was recognised by all Edniburgh lawyers that their apprentice/students were entitled to drop into Mackies (or any of the other well known Coffee Shop in Edinburgh) for a coffee on the way to work after classes! And very pleasant it was to stroll down the Mound, perhaps through the Gardens and along Princes Street with one or two pals exchanging news and views about our employers and their idiosyncrasies! Very few of us could offer to pay for transport. Every penny had to be watched.

ffice, a 25 minute walk took me to the old Quad and surprisingly one could walk from the Old Quad to Coates Crescent in 20 minutes . However it was recognised by all Edniburgh lawyers that their apprentice/students were entitled to drop into Mackies (or any of the other well known Coffee Shop in Edinburgh) for a coffee on the way to work after classes! And very pleasant it was to stroll down the Mound, perhaps through the Gardens and along Princes Street with one or two pals exchanging news and views about our employers and their idiosyncrasies! Very few of us could offer to pay for transport. Every penny had to be watched.

Very soon I came to realise that only Advocates and QC's of the legal profession wore bowler hats.

e) Leisure Activities

I was not long in Edinburgh before I joined tennis and cricket clubs, but by that time the playing season was nearly over. I did manage a few games of tennis in the autumn and resumed in the Spring of 1939. However Manor Cricket Club kept me busy and gave me the opportunity not only of playing in the team but of seeing something of the towns and villages outside Edinburgh. Our first away match was against a Linlithgow team whose pitch was in a lovely park beside a loch and in the shadow of the castle. My first 'hit' I remember sent the ball into the loch - that gave us six runs and another ball had to be found.

During the winter months Ian Mackenzie and I used to watch Hearts football team when playing at home. Ian had a great aunt who lived at the top of a tenement in Gorgie Road and she was pleased to allow us to watch games from her bedroom window - we had in effect a grandstand view without paying! These were the days when Tommy Walker played for Hearts: he was known as the gentleman footballer and he really was the most popular player of all. He was known to be a practising Christian and this showed on and off the field. In due course (I think after the war sometime) he was to become Manager of Hearts. Local 'football derbies' between Hearts and Hibernian whether played at Gorgie Road or Easter Road were always keenly fought and never any sign of hooliganism. Ian and I used to enjoy them greatly. In passing perhaps I should mention that because of my youthful appearance (and lack of height) I never had any difficulty in gaining admission through the 'Boys' entrance: a money saver which I should say also applied at cinemas and theatres!

There were many cinemas and theatres within easy walking distance of Brunstfield and with Ian and sometimes his sister Isobel I enjoyed seeing many good films and plays. The latter were usually in the King's Theatre where we used to queue up for the 'gods' paid the children's entrance fee and sat on concrete steps padded with horse-hair up near the ceiling. I was never happy up there but what could you expect for three pence! Dave Willis starred in his show at the Kings for several weeks that winter and everyone of his audience left singing 'Ma wee gas mask ... an aeroplane an aeroplane away way up a kye .... you'll no get in ma shelter for it's far too wee'.

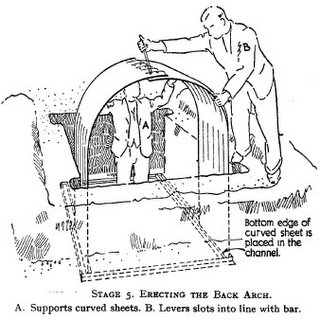

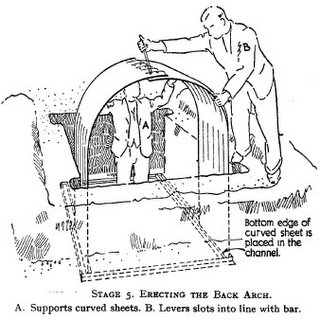

The reference to the shelter arose from the fact that in view of the likelihood of war, (despite Mr Chamberlain's 'Peace in our time' bit of paper) the government were encouraging the people to erect an 'Anderson shelter' in their back gardens to provide shelter, if enemy bombers arrived! The shelters were made of corrugated iron pieces which when bolted together looked rather like a 6' x 6' shed. They were best sunk in a hole in the ground but if this was not possible had to be well covered with soil. They held about six folk and interior arrangements for seating, etc. were as varied as the owners!

The reference to the shelter arose from the fact that in view of the likelihood of war, (despite Mr Chamberlain's 'Peace in our time' bit of paper) the government were encouraging the people to erect an 'Anderson shelter' in their back gardens to provide shelter, if enemy bombers arrived! The shelters were made of corrugated iron pieces which when bolted together looked rather like a 6' x 6' shed. They were best sunk in a hole in the ground but if this was not possible had to be well covered with soil. They held about six folk and interior arrangements for seating, etc. were as varied as the owners!

f) Peoples' Palace

One of the first speakers at the Young Men's Guild in Palmerston Place during the 1938/39 session was the Missionary in charge of the People's Palace in the Cowgate of Edinburgh, namely John Lochore. We had our eyes opened that evening as he spoke of his work among the down and outs who frequented that part of Edinburgh, and the folk who lived in 'single-ends' with as many as twelve in a family, in what was locally called the 'Coogate'. He was supported not by any of the established churches but mainly by individuals who had been moved to used what wealth they had to bring practical Christianity to the poor and the needy. The palace comprised a hall capable of seating up to 400 at one end of which was a stage, a well stocked library, well appointed kitchen and a cafe. Mr Lochore told us of the model lodging houses, the alcoholics, the wife beaters, the poor children being brought up in the most distressing circumstances, the public houses of which four were practically adjacent to his establishment and particularly of his need for volunteers to help with Sunday morning free breakfasts for 400 people, assistance at the various concerts held in the hall on Saturday nights and the cafe where we might expect to serve pie and peas or peas and vinegar. A number of us volunteered for service including my red haired friend Bill Peat, mentioned earlier, who lived out at Morningside. And so began another phase of my education for life.

folk who lived in 'single-ends' with as many as twelve in a family, in what was locally called the 'Coogate'. He was supported not by any of the established churches but mainly by individuals who had been moved to used what wealth they had to bring practical Christianity to the poor and the needy. The palace comprised a hall capable of seating up to 400 at one end of which was a stage, a well stocked library, well appointed kitchen and a cafe. Mr Lochore told us of the model lodging houses, the alcoholics, the wife beaters, the poor children being brought up in the most distressing circumstances, the public houses of which four were practically adjacent to his establishment and particularly of his need for volunteers to help with Sunday morning free breakfasts for 400 people, assistance at the various concerts held in the hall on Saturday nights and the cafe where we might expect to serve pie and peas or peas and vinegar. A number of us volunteered for service including my red haired friend Bill Peat, mentioned earlier, who lived out at Morningside. And so began another phase of my education for life.

On Sunday morning Bill Peat, who had already walked about two miles from his home, met me at the end of my street, at about 6.00 am, and from there we walked across the Meadows down to the Cowgate. On arrival we found that altogether Mr Lochore had nineteen volunteers (all recruited as we had been) from various church groups; most were students. Our first job was to prepare 400 'door step' sandwiches of bread and butter and corned beef. The bread was already sliced as was the corned beef.

This had been done the previous day by the several bakeries and grocers who provided the food gratuitously. Sufficient water to provide 400 pint mugs of tea was already heating when we students arrived. At seven 'o'clock, on the dot the front door was opened and as each person entered he or she was given a pint mug (white enamel). The hall was soon full to capacity of men and women of all ages some of the latter with young children. Mr Lochore opened the proceedings with a blessing on 'the food we are about to receive' and invited all present to enjoy their free breakfast. Sandwiches were passed along the rows and mugs were filled from huge tea pots to which sugar and milk had already been added. If anyone wanted a second sandwich or mug of tea this was freely given. What poor souls we saw there: they had come from the nearby model lodging houses and tenements. There was one rule which each person had to recognise and that was that in exchange for a free breakfast one had to wait on for the service conducted by Mr Lochore. I never saw anyone leave prematurely. The hymn singing - good old Sankey and Moody hymns, of course - was enthusiastic enough to raise the roof. You might have been 'as tight as a puggie' the night before: that made no difference to your praise of the Almighty. Mr Lochore's sermons were always of an uplifting nature and listened to with close attention and frequent cries of 'Hallelujah'. Students who felt so inclined were given the opportunity from time to time of addressing the gathering and I had the privilege of doing so on at least one occasion! I will remember my first text (all preachers in those days began with a text! was 'Come unto me all you that labour and are heavy laden'. To my astonishment I was given a resounding cheer as I finished! But, later, others had the same experience.

After breakfast came the tidying up of the hall and the cleaning and drying of utensils and the 400 or so mugs!

The kitchen too was left in ship shape condition - a lady from Camely Bank whose name, sadly, I forget made it her special duty to see that 'Godliness' also meant 'cleanliness'.

By 8.30 am I was back in my digs where Mrs MacKenzie had my 'full Scottish breakfast' as it is now called all ready and waiting the moment I emerged washed and shaved from the bathroom.

There was a duty roster for Saturday nights at the Palace Cafe which ensured that we did not have to attend every Saturday; this gave opportunity for theatre going, dancing etc. Customers were able to buy a pie for tuppence (2d), a pie and peas for thruppence (3d), peas and vinegar on a saucer for one penny and sandwiches of the door-step kind for 3d. Tea cost one penny a cup, cocoa and Ovaltine tuppence and a bowl of soup 3d. Behind the counter we were kept busy I can assure you both in the selling of food and in cleaning up. Keeping the customers happy often had problems, espacially with any who were under the influence of alcohol.

I use that word because most of our customers could not afford whisky or gin, they drank metholated spirits, liquid boot polish or brasso! It was pitiful to see so many lying in the gutter on a Saturday night but we had been told by the police never to touch any of them. Bill Peat and I once tried to stop a fellow who was repeatedly striking a woman with a stick and cursing all the time. But we were soon stopped - the lady concerned turned on us calling us all the so and so's on God's earth and warning us not to interfere between husband and wife. On future occasions we left such couples to do as they pleased!

On my first duty in the cafe an old tramp pestered me to give him the trousers I was wearing but old Mr Lochore came to my rescue and saved the day for me.

All the recently joined helpers were invited to go down to the Cowgate one Sunday afternoon in order to see for ourselves what a 'Model' really looked like from the inside. Again we were unprepared for what we saw. In one large room there were 12 hawser type ropes slung across the room from hooks on either side. Each was about 3 feet high at the middle (i.e. the lowest part) rising to 4 feet 6 inches at the wall. It cost one penny per night to 'sleep' by leaning on a hawser with ones arms hanging on the side away from the torso. For three pence one could sleep on a low bed made of wood with a dirty old blanket and pillow, but, for six pence a spring bed with paliasse plus blanket and pillow or simply a space on the floor similarly equipped was available. I never saw such appalling conditions ever before. Yet even in this so-called enlightened age people are sleeping rough, outside, in cardboard boxes. But the old book says "the poor you have always with you". A senior social worker speaking of his role in the community once said to me "the word 'poor' in that context means 'poor souls'. - undoubtedly he was right.

Many local amateur dramatic groups and choirs used to come to the People's Palace of a Saturday evening to entertain our clientele. One such visit I well remember: the Corstorphine Ladies Choir, well known in the District for their beautiful singing offered their services to Mr Lochore who readily accepted. There were about 40 ladies in the choir so it was necessary to borrow chairs from the Pleasance (where a similar missionary organisation laboured). The chairs were set out on the stage - four rows of ten. The choir all wore beautiful white dresses. With some of my friends I was seated in the front row of the hall and when at the interval the ladies rose from their chairs and turned towards the library where they were to have tea, we were horrified to realise that the chair seats had not been cleaned and indeed must have been in a sooty environment! speak about the 'black bottom' - there were 40 of them. Mr Lochore had plenty to say to the boys who had arranged the chairs without taking steps to clean them!

So, during the period from early October 1938 until June 1939 I was privileged to be associated with the People's Palace Mission. At that time there was a strong feeling among those interested in the glorious work he was doing that John Lochore should be allowed by the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland or any other competent body to use the title 'Reverend'. A good many years were to elapse before this was eventually agreed but I have no recollection of the details.

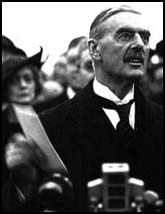

g) War in the offingWherever folk met together, even young folk, during the late 30's, their talk eventually turned to discussion about the events in Europe and the frightening demands and activities of the Nazis and their leader L/Cpl. Adolf Hitler. On the wireless (not yet become 'radio') the Chancellor of Germany could be heard 'bawling and shouting like a madman', as my father said, almost every evening and if he wasn't on the Lord Hawhaw', a traitor if every there was one, delighted in telling us of the benefits of National Socialism, the need for the Germans to have 'Lebensraum, the wickedness of the capitalist nations and the evil influence which the Jews had exerted all over the world and particularly in Europe for centuries.

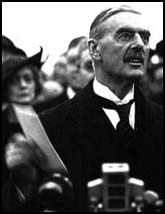

In Edinburgh the awful facts of the situation in Germany very soon became apparent to those of my age for there was a steady influx of refugees who could tell us from personal experience of the satanic forces being nurtured within Germany and the vile treatme nt being meted out to those who were not of Aryan stock. The Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, went out to meet with Hitler and came back brandishing for all the press photographers to see a bit of paper which he said that the agreement he had reached with Hitler meant that there would be 'peace in our time'! If ever anyone was 'conned' old Chamberlain certainly was. I think we all knew that the black clouds over Europe would inevitably lead to war. But with my fellows in the Young Men's Guild I was a pacifist! However after many discussions in the office, in coffee shops, in the Old Quad and the Y.M.G. as well, I came to the conclusion that if my own dear Mother was to be in danger from these Nazis. I would have no alternative but to fight. My father and grandfather had been in the R.N.V.R. and I decided to try for a Commission. The University O.C.T. was fully manned: Ramsay and Hector were already members: so an army commission was ruled out. I therefore went to Evening classes in navigation and seamanship at Leith Nautical College: a pass in these subjects in June 1939 would allow me to become a sub-lieutenant. Every Tuesday and Thursday evening saw me on the tram away down to Leith where I enjoyed the classes greatly. My ambitions in this regard were dashed when the government announced that all those of my sort of age group who were not enlisted in one or other of the services by the end of March 1939 would be 'called up' and be required to serve for the whole of six months on a full time basis! This fairly set the cat among the pigeons as far as Law Apprentices were concerned. Bob Coutts and I had a meeting with old Nommo Smith. He advised us to join the Territorial Army which required only one attendance per week - a Friday evening - and two weeks at camp in the summer. Thus would our service as Apprentices be saved. I notified the Nautical College of my problem and then withdrew from the evening classes. Then one evening in March 1939 Bob and I with, it seemed to us, hundreds of other young men, gathered in the T.A. Drill hall at Grindley Street, Edinburgh and swore allegiance to King and Country , on becoming gunners in the 78th Field Regiment R.A. (T.A.). Very soon we were issued with all the paraphernalia of a soldier including 'drawers woollen long, Boots, black, (Army), a housewife (called a Hussif) containing all that was required for sowing on buttons, mending tears, darning etc. a brass button stick (Used to prevent polish soiling the uniform when cleaning the brass buttons) and so on! I still have in 1995 the brush issued to me then for polishing my boots; and it is still in use.

nt being meted out to those who were not of Aryan stock. The Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, went out to meet with Hitler and came back brandishing for all the press photographers to see a bit of paper which he said that the agreement he had reached with Hitler meant that there would be 'peace in our time'! If ever anyone was 'conned' old Chamberlain certainly was. I think we all knew that the black clouds over Europe would inevitably lead to war. But with my fellows in the Young Men's Guild I was a pacifist! However after many discussions in the office, in coffee shops, in the Old Quad and the Y.M.G. as well, I came to the conclusion that if my own dear Mother was to be in danger from these Nazis. I would have no alternative but to fight. My father and grandfather had been in the R.N.V.R. and I decided to try for a Commission. The University O.C.T. was fully manned: Ramsay and Hector were already members: so an army commission was ruled out. I therefore went to Evening classes in navigation and seamanship at Leith Nautical College: a pass in these subjects in June 1939 would allow me to become a sub-lieutenant. Every Tuesday and Thursday evening saw me on the tram away down to Leith where I enjoyed the classes greatly. My ambitions in this regard were dashed when the government announced that all those of my sort of age group who were not enlisted in one or other of the services by the end of March 1939 would be 'called up' and be required to serve for the whole of six months on a full time basis! This fairly set the cat among the pigeons as far as Law Apprentices were concerned. Bob Coutts and I had a meeting with old Nommo Smith. He advised us to join the Territorial Army which required only one attendance per week - a Friday evening - and two weeks at camp in the summer. Thus would our service as Apprentices be saved. I notified the Nautical College of my problem and then withdrew from the evening classes. Then one evening in March 1939 Bob and I with, it seemed to us, hundreds of other young men, gathered in the T.A. Drill hall at Grindley Street, Edinburgh and swore allegiance to King and Country , on becoming gunners in the 78th Field Regiment R.A. (T.A.). Very soon we were issued with all the paraphernalia of a soldier including 'drawers woollen long, Boots, black, (Army), a housewife (called a Hussif) containing all that was required for sowing on buttons, mending tears, darning etc. a brass button stick (Used to prevent polish soiling the uniform when cleaning the brass buttons) and so on! I still have in 1995 the brush issued to me then for polishing my boots; and it is still in use.

In June, by which time we had been taught how to march, as the Artillery did in columns of three, basic gun drill on an old 18 pdr., semaphore signalling (which I had learned in scouts) and how to use the 'Don 5' telephone, I was ordered to be ready to go with the advance party to the firing camp at Trawsfynnd, near Blenau Ffestiniog in North Wales. And so it was that at the end of June I donned my uniform walked out of my digs and reported for duty; a soldier proper! Sitting in the passenger seat of a 15 cwt army truck driven by Bob Anderson a scavenger, in Civvy street, who became a close friend, we drove south with six or seven other vehicles through torrential rain for two days. The driver and the passenger had separate wind screens each about 12 inches square; the passenger operated a lever which moved the two wipers across the glass and this was of course my duty. You can imagine how tired I was after only a few miles through heavy rain. There was no roof above our heads and by the time we reached Carlisle and stopped for the night our clothes were saturated. Bob seemed to know how to achieve the impossible - next morning he appeared at my bed with my clothes all nicely dry and warm!

As the advance party we had to 'take over' the camp and all its equipment as listed on an inventory of the Camp Commandants' staff. Now I found why I had been selected for the advance party - my duty was to check the several inventories along with the Regimental Quarter-Master Sergeant. This was not unpleasant as at least it kept me indoors away from the continuous rain. The Commanding Officer (Lt Col. Cross) told me that he had decided to promote me to the rank of Unpaid Acting Lance Bombadier and to place me in the Quarter-Master's office. Apart from the R.Q.M.S. and myself the members of the staff were my friend the truck driver Bob Anderson and Joe Salton who was employed in Younger's Brewery down the Canongate in Edinburgh. They had been in the 'Terris' for many years, were much older than I was, and knew all the tricks of the quarter-master trade! They accepted my promotion to L/Bdr as if they expected it and we became great friends. Being in the Q.M store and office meant that I was spared from the continuous rain with which the Regiment had to contend for the duration of the camp. The main body arrived a week after the advance party and remained for two weeks. We, the advance party, now became the 'Rear Party' which kept us in North Wales for another few days. We were away from Edinburgh for a whole month. So much for old Nimmo's 'fortnight's summer camp'.

During that camp we in the Quarter Master's Stores lived like the proverbial Lords with fillet steak and chips for supper every night and the best of everything else. For those who don't know, all army supplies from guns, rifles, and ammunition to butter, jam, uniforms and blankets were obtained and distributed by the Quarter Master and his staff! One of my principal jobs was to set up a ledger listing the number rank and name of every 'other rank' in the Regiment - there were 550 - and to 'tick off' in the relevant columns every piece of uniform and equipment issued to him. As a result I was soon to come to know every man in the Regiment and most of their numbers. Mine, by the way was 899080. What had been issued in Edinburgh had to be brought back to the R.Q.M.S. in camp for checking and entering up in wee Cameron's Ledger!

On returning to Edinburgh I was ordered to wear my uniform every day to the office (the University had closed for the Summer vacation by this time) in case of emergency. Bob Coutts returned as a full Sergeant but did not have to wear his uniform until towards the end of August when we were all embodied into His Majesty's Army and became full time soldiers.

And so to War....Click here >> Chapter 13

Edinburgh

a) Arrival

On arriving at Princes Street Station in Edinburgh I proceeded with my bowler hat on my head (nowhere else to put it) my suitcase of clothes in my right hand, and sports bag (containing mainly cricket and tennis gear) in the other to climb towards Princes Street and the No. 9 tram which would take me to

Bruntsfield where my landlady Mrs Jess MacKenzie lived. The wind in the Waverly steps was gusting at least force six and as I was almost at the top the wind took off my bowler hat and carried it over trams, cars and the Woolworth building (2 storey high) out of my sight to an unknown destination. I made no effort to retrieve it - how could I encumbered with two cases and knowing nothing of the geography of Edinburgh?

Bruntsfield where my landlady Mrs Jess MacKenzie lived. The wind in the Waverly steps was gusting at least force six and as I was almost at the top the wind took off my bowler hat and carried it over trams, cars and the Woolworth building (2 storey high) out of my sight to an unknown destination. I made no effort to retrieve it - how could I encumbered with two cases and knowing nothing of the geography of Edinburgh?Having stepped inside the first No. 9 tram that came along I sat downstairs, paid my fair of 1 penny and admired the wonders of Princes Street marvelling at the large numbers of folk who were walking on the pavements and in gardens. What did they all do for a living? The tram turned left at St. John's Church at the west end of Princes Street and proceeded up Lothian Road. The conductor told me where to get off for Bruntsfield Avenue. When I reached No. 10 it was to find that I had to pull a brass knob marked 'Mackenzie' - thereupon the main or front door opened (of its own accord?) and I entered. High above me I heard the welcoming voice of her who was to become my second mother - Jess Mackenzie. To reach her flat one had to climb 78 steps - the highest I had ever been!

Immediately I was made to feel at home. Her daughter Isobel 14 years old and son Ian 12 were of course known to me as they used to come up to Ardersier to holiday with their grandparents Mrs MacKenzie's father and mother. Because there were two other lodgers in the four bedroom flat the front or sitting room had been allotted to the new lodger. This was the biggest room in the flat with fine furniture including a bed settee for the lodger. Yes. it was very comfortable. The other two lodgers one a Civil Servant (name of Sibbald) and the other a hair dresser (Jean was her name) had chosen to have their meals in their respective rooms but I decided I would dine with the family in the kitchen. And so commenced a year of hard work and great happiness.

I soon became the chief dish dryer! Mrs MacKenzie was a fine cook and baked scones, cakes, cream sponges to make one's mouth water. Sibbald and Jean had their meals taken in to them on trays. Ian did one, Isabel the other. The bathroom was allocated on a strict time basis: Sibbald at 7.30 am, Jean at 7.45 am and myself at 8.00 am. During the whole year that I lived in that home I never saw once either of the other lodgers. Strange but true. Their names were constantly mentioned, naturally, as they formed part of the menage but they truly 'kept themselves to themselves'. For board and lodging I had to pay £1-5/-(One pound and five shillings) per week and 2/6d (half a crown) for laundry. Apart from my bursary of £30 my salary with the Edinburgh firm was to be 10/- (ten shillings) per week. Most of the bursary money would be taken up with matriculation and class and examination fees in addition to which the prescribed text books, note books and such like would have to be paid for? What faith we had in those days!

b) Palmerston Place ChurchI had arrived on a Saturday and Mrs Mackenzie invited me to attend her church which was nearby. I did this but found the minister very dull after my beloved Mr Maceleroy. So I was told that the place for me was Palmerston Place Church where the Minister was Rev. William C. MacDonald M.A. and that I should go there that evening. On arrival at this large church in the West End I decided to go up into the balcony. At the top of the winding stair case a red haired tall young man of my own age invited me to help him to hand

out the hymn books of which there seemed to be hundreds piled up against the walls. Never had I seen so many people, mostly of student age enter the portals of a church. How they were seated I had no idea but when the number of hymn books had diminished to a dozen or so Bill Peat (by this time I knew his name!) told me we had better go inside and 'pack them in'. I had no idea what I was in for but there as we entered was a sea of faces before me! There was little option but to do as Bill had asked me and by the time we ourselves had to sit down there was room only on the balcony steps. What an uplifting experience that was. As I had thought most of the congregation that evening, and as I was to find out later every Sunday evening, the church was packed with students eager to hear Willie MacDonald preach. The singing 'raised the roof' and during the sermon you could hear the proverbial pin drop. Remember we were living in the age when the German Jack Boot was tramping across Europe, Hitler was shouting his obscenities over the radio, Jewish people were being terrorised and many arrived in Britain telling of the obscenities already being perpetrated by the Nazis. Willie MacDonald had been a student of that great theologian Karl Barth in Switzerland. Barth had held Professorship at Gottigen and Bonn and his influence was such that he changed the whole outlook of Protestant theology on the Continent. He stressed the absolute difference between God and man, man's inherent inability to solve his own problems and his complete dependence on revelation and grace offered to man in the person of Jesus Christ. This was what Willie preached in sermon after sermon and in the most acceptable manner. No wonder young folk came from all over Edinburgh to hear his sermons. Having joined the Church in Ardersier I decided that evening to 'transfer my lines to Palmerston Place and soon was a member there. I also joined the young Men's Guild in which we had 70 or so members - at that time all pacifists! Meetings largely took the form of debates or talks by visiting 'experts' or members themselves. I had the privilege of reading a paper on the subject of Crime and Punishment - reading it some 50 years later I found that my views had changed little although my style of presentation had. Another subject on which I made the motion and therefore spoke at length was the 'Iniquitous Disparity between the income levels of miners and fishermen and the professional classes!' I remember arguing that Miners and Fisherman should have a guaranteed wage of £1,000 per annum! The motion was carried. One of our members was the Rev Stanley Mair the Assistant Minister. He had a voice like a trumpet and it was a joy to listen to him making a point. Some time after this a number of us persuaded him to speak at the Mound when in those days speakers on all manner of subjects from socialism to atheism 'spouted forth' on a Sunday evening. We persuaded the Church of Scotland to let us have their soap box which was agreed on condition that it was returned to St. Cuthbert's Church after use. When we arrived the Minister for that evening seemed to be glad to hand over to Stanley. No wonder - the noise of speakers shouting was horrendous. Standing mounted on the box, he took off his jacket, rolled up his sleeves, took off his red tie and literally 'bellowed' at the crowds gathered round the other speakers. So loud was his voice and so compelling his words that very soon he was surrounded by folk who had even given up listening to the others at the Mound: Even the Salvation Army Band ceased playing in order to hear this - new voice. From then on Stanley Mair's oratory could be heard at the Mound regularly, indeed he became one of the 'star' speakers on a Sunday evening until the forthcoming conflict saw him like the rest of us away on active service.

out the hymn books of which there seemed to be hundreds piled up against the walls. Never had I seen so many people, mostly of student age enter the portals of a church. How they were seated I had no idea but when the number of hymn books had diminished to a dozen or so Bill Peat (by this time I knew his name!) told me we had better go inside and 'pack them in'. I had no idea what I was in for but there as we entered was a sea of faces before me! There was little option but to do as Bill had asked me and by the time we ourselves had to sit down there was room only on the balcony steps. What an uplifting experience that was. As I had thought most of the congregation that evening, and as I was to find out later every Sunday evening, the church was packed with students eager to hear Willie MacDonald preach. The singing 'raised the roof' and during the sermon you could hear the proverbial pin drop. Remember we were living in the age when the German Jack Boot was tramping across Europe, Hitler was shouting his obscenities over the radio, Jewish people were being terrorised and many arrived in Britain telling of the obscenities already being perpetrated by the Nazis. Willie MacDonald had been a student of that great theologian Karl Barth in Switzerland. Barth had held Professorship at Gottigen and Bonn and his influence was such that he changed the whole outlook of Protestant theology on the Continent. He stressed the absolute difference between God and man, man's inherent inability to solve his own problems and his complete dependence on revelation and grace offered to man in the person of Jesus Christ. This was what Willie preached in sermon after sermon and in the most acceptable manner. No wonder young folk came from all over Edinburgh to hear his sermons. Having joined the Church in Ardersier I decided that evening to 'transfer my lines to Palmerston Place and soon was a member there. I also joined the young Men's Guild in which we had 70 or so members - at that time all pacifists! Meetings largely took the form of debates or talks by visiting 'experts' or members themselves. I had the privilege of reading a paper on the subject of Crime and Punishment - reading it some 50 years later I found that my views had changed little although my style of presentation had. Another subject on which I made the motion and therefore spoke at length was the 'Iniquitous Disparity between the income levels of miners and fishermen and the professional classes!' I remember arguing that Miners and Fisherman should have a guaranteed wage of £1,000 per annum! The motion was carried. One of our members was the Rev Stanley Mair the Assistant Minister. He had a voice like a trumpet and it was a joy to listen to him making a point. Some time after this a number of us persuaded him to speak at the Mound when in those days speakers on all manner of subjects from socialism to atheism 'spouted forth' on a Sunday evening. We persuaded the Church of Scotland to let us have their soap box which was agreed on condition that it was returned to St. Cuthbert's Church after use. When we arrived the Minister for that evening seemed to be glad to hand over to Stanley. No wonder - the noise of speakers shouting was horrendous. Standing mounted on the box, he took off his jacket, rolled up his sleeves, took off his red tie and literally 'bellowed' at the crowds gathered round the other speakers. So loud was his voice and so compelling his words that very soon he was surrounded by folk who had even given up listening to the others at the Mound: Even the Salvation Army Band ceased playing in order to hear this - new voice. From then on Stanley Mair's oratory could be heard at the Mound regularly, indeed he became one of the 'star' speakers on a Sunday evening until the forthcoming conflict saw him like the rest of us away on active service.c) Kinimont & Maxwell, W.S.

On the Monday following my arrival in Edinburgh I reported to my new office at No. 11 Coats Crescent, Edinburgh. Mrs MacKenzie had told me how to get there and as it was quite near Palmerston Place I had a preview on the Sunday evening noting carefully that it would take me 20 minutes to walk along Shandwick Place and up Lothain Road, Earl Grey street and Bruntsfield Road to my lodgings. Downhill would be achieved in less time. So, as the tram fare to the West End was one penny I decided to walk to the office. I was wearing my three guinea suit when I arrived and was led to the office of Robert W. Martin, W.S. the junior partner. He gave me a warm welcome and asked the Managing Clerk a comparatively young man, Duncan Livingstone MacDonald, Solicitor, to come and meet the new apprentice. This he did very warmly and then took me to meet the Cashier, her staff and then the typists. Eventually I was guided into the apprentices' room. There were three others and to my great embarrassment all were wearing tatty old jackets and flannel trousers! You can imagine how I felt all dressed up as I was in my fine new suit. At lunch time I walked home and changed into informal clothes, even so my new tweed jacket and flannels 'stood out a mile' compared to the others with whom I was to work. The Dickensian desk at which we sat on high stools made me wish I was back at my 'proper' desk in Inverness. However one can get accustomed to most things in life and so it was here.

I was allotted work relating to several Executries and Trusts and was taken aback by the values. In Inverness we had dealt with tens of thousands with the occasional six figure estates but here all I had before me were for six figure sums. The K & M clients must be very wealthy! As indeed most of them were. Two of the other apprentices, Ramsay (he was always addressed by his surname) Hector Ross the son of a Hill Street publican, were in their third year of the B.L. degree while Bob Coutts from Kinross was in his second year. They all proved to be very helpful to me and Bob became a firm friend outwith office hours. The Cashier Miss Hamilton was, to me, an old lady who ruled the cash room and the typists also with the proverbial rod of iron.

The senior partner of the firm was Francis Celement Nimmo Smith, W.S. who used to arrive in a chauffeur driven Rolls Royce at 10.00 am was then enclosed with Bertie (as he was affectionately called) Martin and sometimes also D.L.M. the Managing Clerk until 11.00 am or 11.30 am going, as I was told, going over the mail. Soon after his arrival the office caretaker Mrs Mackenzie a lady from Lochiver used to ascend from her basement dwelling bearing a silver tray on which she carried a silver tea service and the best china. This she took in to the boss's room. I may say it was from our dear old Mrs Mackenzie that I first tasted china tea!

Soon after 11.00 am F.C.N.S. (as we called him) departed in his limousine for lunch at a golf club at a place called 'Gillane'. I was soon to discover that what the map told me was 'Gullane', in Edinburgh was pronounced in a more genteel fashion! F.C.N.S. never once in the time I was with K and M appeared in the office except to 'go over the mail' as mentioned above.

After I had been in Edinburgh almost one month D.L.M. told me that the chief wanted to see me. When I entered his room he welcomed me to the firm and wished me well. He already knew all about me and my back ground and was particularly interested in the fact that I had already joined a cricket club and a tennis club in Edinburgh. He was delighted to hear that not only had I seen the Australians play the Northern Counties in Forres but had 'caught out' Don Bradman. In reply to one question I told him of my bursary and the salary being paid by his firm.

He asked me how I was going to survive in Edinburgh when my outlays so far exceeded my income. I remember telling him that my parents were people of great faith! He knew of course all about the sad economic state of the fishing industry at that time. (I already knew he had shares in two fish processing companies!) 'Now' he said 'you are to tell Miss Hamilton to pay you twenty-five shillings a week in addition to your salary and that will pay for your digs'. I thanked him most humbly and on leaving his room went straight to Miss Hamilton in her glass compartment to tell her my good news. She almost had a heart attack at my effrontery. When I assured her I really was telling the truth she rushed into Nimmo's room but soon returned. She said I was a very lucky young man, I was to tell nobody of the senior partner's generosity, as I was now to be the highest paid of all the employees except the Managing Clerk, D.L.M. And so I had 10 shillings per week from which had to be deducted ten pence as my contribution to the Inverness County Benefit Society ( a sort of fore runner of the N.H.S.) leaving me with nine shillings and two pence from which my laundry bill was paid. In other words my net income for the rest of my pre-war days with K & M was 6/8d (six shillings and eight pence per week). Remember a bar of chocolate cost only tuppence and the tram from Waverley to my digs in Bruntsfield cost one penny.

With K & M my work load extended to Income Tax in which I found myself being regarded as an expert (all thanks to the Civil servants in the Tax office at 42 Union Street, Inverness and the School of Accountancy), some minor conveyancing for clients buying bungalows for £300 to £500, valuation of investment portfolios for our many wealthy clients and the occasional Court of Session action. Ramsay and Hector were given the job of introducing me to Parliament House and the Court procedures followed there. I do not remember one small debt summons or any other action in the Sheriff Court: our clients were 'above that sort of thing!;.

d) Edinburgh University (Pre war)Early in October 1939 I proceeded to the University -twenty five minutes walk from my digs, across the Meadows to George IV bridge, down Chambers Street and right into 'the Bridges' where the first opening on the right gave access to the beloved 'Old Quad'. I obtained my matriculation card and enrolled for the classes in Civil (otherwise Roman) Law and Jurisprudence ('science of law' no less) each being three term courses and put myself down for the class in Forensic Medicine which would commence in January and last for only two terms. Now I was all set to study law! The office, of course, recognised that Apprentices were also students who required time off to attend classes. Civil Law classes commenced at 9.00 am when an old (very old) Professor Mackintosh sat at a desk and read notes which he had first written when appointed to the Chair forty years previously! We were expected to take notes and if my writing is bad you can blame these classes. The lecture room was laid out with pews and book boards in terrace format the back row being, I'm sure, ten feet above the Professor! Because of my stature I could not hope to lean my note book on the book board provided, it was so high in relation to the seat that I could not possibly write and chose to sit on the steps with note book supported on my knees scribbling away like mad while the Prof. read his notes at a speed of about 250 words per minute. At the end of the first week a number of us asked the old boy if we could have copies of his lectures or even a précis issued to us. The answer was that this had never been done before and he was not going to start now!

Like most of my fellow students I had been able to purchase, in James Thin's second hand book shop in Chambers Street, copies of Justinian's Institutes as well as those of Gaius at a price of 1/3d each. They were no longer being published yet they were prescribed reading. These books were set out in columnar form with the Latin text on the left and English translation on the right - thank goodness. Accordingly while at exam time one could readily answer questions in English one could also translate passages from Latin into English - assuming always that one had done the necessary work.

Sadly Professor Mackintosh died early in the third term and his place was taken by the Dean of the Faculty, Professor Matthew Fisher. He simply took over his predecessor's notes and read them to us! He also decided that the degree exams would 'in the circumstances', be deferred until September. That was to give us more time for study or so he said!

For jurisprudence the text book was also available in James Thin's at a cost of one shilling. Classes commenced at 1.30 p.m. and continued for no more than 40 minutes - long enough for most of us who regarded the subject as somewhat esoteric or nebulous and of no use whatsoever in the hurly burly of the Sheriff Court or so far as any of us could judge at that stage in our careers, the Court of Session. However it was a required subject for degree purposes. Many a weary evening I spent in the George IV Library trying to assimilate the mysteries of jurisprudence. I remember the professor (I think Guthrie who may have become Lord Guthrie) telling even he was not sure why the subject was mandatory - he had wondered that when a student too-his job was to lecture on it!.

The classes in Forensic Medicine (when they commenced in January 1939) were held in the medical faculty premises and were attended by hoards of medical students and a fair number of law students. Classes commenced at 4.30 p.m. and usually lasted for one hour. On a number of occasions classes were convened earlier in the day or even on a Saturday morning. These were always 'practical' in the sense that there in the middle of the room on the table lay the body of someone who had very recently been murdered in some devilishly foul manner or poisoned over a long or short period of time.

I omit the gruesome details of these post mortems. Suffice it to say that while the medical students would crowd around the body to see closely what the pathologist was up to many of the law students either passed out or had to leave the room. Perhaps it was good experience for what many had to experience during the war.

Professor Sidney Smith had become well known at the time of the notorious 'Buck Ruxton' murder trial and he delighted in showing us 'samples' in jars of formalin. At one time he had been in the service of the Egyptian government and had managed to solve some mysterious murders. How he delighted in relating the sordid details!

You will remember that a 20 minute walk took me from my digs to the o

ffice, a 25 minute walk took me to the old Quad and surprisingly one could walk from the Old Quad to Coates Crescent in 20 minutes . However it was recognised by all Edniburgh lawyers that their apprentice/students were entitled to drop into Mackies (or any of the other well known Coffee Shop in Edinburgh) for a coffee on the way to work after classes! And very pleasant it was to stroll down the Mound, perhaps through the Gardens and along Princes Street with one or two pals exchanging news and views about our employers and their idiosyncrasies! Very few of us could offer to pay for transport. Every penny had to be watched.

ffice, a 25 minute walk took me to the old Quad and surprisingly one could walk from the Old Quad to Coates Crescent in 20 minutes . However it was recognised by all Edniburgh lawyers that their apprentice/students were entitled to drop into Mackies (or any of the other well known Coffee Shop in Edinburgh) for a coffee on the way to work after classes! And very pleasant it was to stroll down the Mound, perhaps through the Gardens and along Princes Street with one or two pals exchanging news and views about our employers and their idiosyncrasies! Very few of us could offer to pay for transport. Every penny had to be watched.Very soon I came to realise that only Advocates and QC's of the legal profession wore bowler hats.

e) Leisure Activities

I was not long in Edinburgh before I joined tennis and cricket clubs, but by that time the playing season was nearly over. I did manage a few games of tennis in the autumn and resumed in the Spring of 1939. However Manor Cricket Club kept me busy and gave me the opportunity not only of playing in the team but of seeing something of the towns and villages outside Edinburgh. Our first away match was against a Linlithgow team whose pitch was in a lovely park beside a loch and in the shadow of the castle. My first 'hit' I remember sent the ball into the loch - that gave us six runs and another ball had to be found.

During the winter months Ian Mackenzie and I used to watch Hearts football team when playing at home. Ian had a great aunt who lived at the top of a tenement in Gorgie Road and she was pleased to allow us to watch games from her bedroom window - we had in effect a grandstand view without paying! These were the days when Tommy Walker played for Hearts: he was known as the gentleman footballer and he really was the most popular player of all. He was known to be a practising Christian and this showed on and off the field. In due course (I think after the war sometime) he was to become Manager of Hearts. Local 'football derbies' between Hearts and Hibernian whether played at Gorgie Road or Easter Road were always keenly fought and never any sign of hooliganism. Ian and I used to enjoy them greatly. In passing perhaps I should mention that because of my youthful appearance (and lack of height) I never had any difficulty in gaining admission through the 'Boys' entrance: a money saver which I should say also applied at cinemas and theatres!

There were many cinemas and theatres within easy walking distance of Brunstfield and with Ian and sometimes his sister Isobel I enjoyed seeing many good films and plays. The latter were usually in the King's Theatre where we used to queue up for the 'gods' paid the children's entrance fee and sat on concrete steps padded with horse-hair up near the ceiling. I was never happy up there but what could you expect for three pence! Dave Willis starred in his show at the Kings for several weeks that winter and everyone of his audience left singing 'Ma wee gas mask ... an aeroplane an aeroplane away way up a kye .... you'll no get in ma shelter for it's far too wee'.

The reference to the shelter arose from the fact that in view of the likelihood of war, (despite Mr Chamberlain's 'Peace in our time' bit of paper) the government were encouraging the people to erect an 'Anderson shelter' in their back gardens to provide shelter, if enemy bombers arrived! The shelters were made of corrugated iron pieces which when bolted together looked rather like a 6' x 6' shed. They were best sunk in a hole in the ground but if this was not possible had to be well covered with soil. They held about six folk and interior arrangements for seating, etc. were as varied as the owners!

The reference to the shelter arose from the fact that in view of the likelihood of war, (despite Mr Chamberlain's 'Peace in our time' bit of paper) the government were encouraging the people to erect an 'Anderson shelter' in their back gardens to provide shelter, if enemy bombers arrived! The shelters were made of corrugated iron pieces which when bolted together looked rather like a 6' x 6' shed. They were best sunk in a hole in the ground but if this was not possible had to be well covered with soil. They held about six folk and interior arrangements for seating, etc. were as varied as the owners!f) Peoples' Palace

One of the first speakers at the Young Men's Guild in Palmerston Place during the 1938/39 session was the Missionary in charge of the People's Palace in the Cowgate of Edinburgh, namely John Lochore. We had our eyes opened that evening as he spoke of his work among the down and outs who frequented that part of Edinburgh, and the

folk who lived in 'single-ends' with as many as twelve in a family, in what was locally called the 'Coogate'. He was supported not by any of the established churches but mainly by individuals who had been moved to used what wealth they had to bring practical Christianity to the poor and the needy. The palace comprised a hall capable of seating up to 400 at one end of which was a stage, a well stocked library, well appointed kitchen and a cafe. Mr Lochore told us of the model lodging houses, the alcoholics, the wife beaters, the poor children being brought up in the most distressing circumstances, the public houses of which four were practically adjacent to his establishment and particularly of his need for volunteers to help with Sunday morning free breakfasts for 400 people, assistance at the various concerts held in the hall on Saturday nights and the cafe where we might expect to serve pie and peas or peas and vinegar. A number of us volunteered for service including my red haired friend Bill Peat, mentioned earlier, who lived out at Morningside. And so began another phase of my education for life.

folk who lived in 'single-ends' with as many as twelve in a family, in what was locally called the 'Coogate'. He was supported not by any of the established churches but mainly by individuals who had been moved to used what wealth they had to bring practical Christianity to the poor and the needy. The palace comprised a hall capable of seating up to 400 at one end of which was a stage, a well stocked library, well appointed kitchen and a cafe. Mr Lochore told us of the model lodging houses, the alcoholics, the wife beaters, the poor children being brought up in the most distressing circumstances, the public houses of which four were practically adjacent to his establishment and particularly of his need for volunteers to help with Sunday morning free breakfasts for 400 people, assistance at the various concerts held in the hall on Saturday nights and the cafe where we might expect to serve pie and peas or peas and vinegar. A number of us volunteered for service including my red haired friend Bill Peat, mentioned earlier, who lived out at Morningside. And so began another phase of my education for life.On Sunday morning Bill Peat, who had already walked about two miles from his home, met me at the end of my street, at about 6.00 am, and from there we walked across the Meadows down to the Cowgate. On arrival we found that altogether Mr Lochore had nineteen volunteers (all recruited as we had been) from various church groups; most were students. Our first job was to prepare 400 'door step' sandwiches of bread and butter and corned beef. The bread was already sliced as was the corned beef.